Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Laingsburg is a small Karoo town 250 km inland from Cape Town. The Buffels River flows along the western side of the town, with ‘flow’ being a rather abstract term most of the time. In 1981, this river flooded with catastrophic results and the suddenness with which the small town was annihilated by flood waters still resonates today. The risk of severe flooding remains an ever-present threat to Laingsburg, and while it seems that although the disaster is not specifically mentioned in formal municipal planning documents in the post-1994 era, it has not been forgotten by the townsfolk as attested by YouTube videos at the 30 year (2011) and 40 year (2021) anniversaries of the disaster.

The Buffels River catchment

The Buffels River catchment includes the Buffels, Wilgenhout and Baviaans rivers, and lies in the rain shadow of the Langeberg, Swartberg and Witteberg Mountains. This means that the catchment is dry for years on end, although since the 1700s, it has been noted for its periodic flood events. On occasion, when a High Pressure System occurs off shore, massive amounts of moist air from the coast can be forced over the mountains and cause excessive rain on the other side in the Buffels River catchment (Hoorn 2021). When this happens, the three rivers in the catchment become roaring monsters that converge at the outskirts of Laingsburg. On the 25th January 1981, such an event occurred. The co-joined Buffels River burst its banks because of unprecedented rainfall in the catchment area and flood waters and mud swept through Laingsburg, at places reaching a level 10-metres above its usual flow-level. Households began to respond by placing sandbags in their doorways, but soon these were inadequate, houses began to collapse and people had to leave their homes. Some left this too late and were swept away.

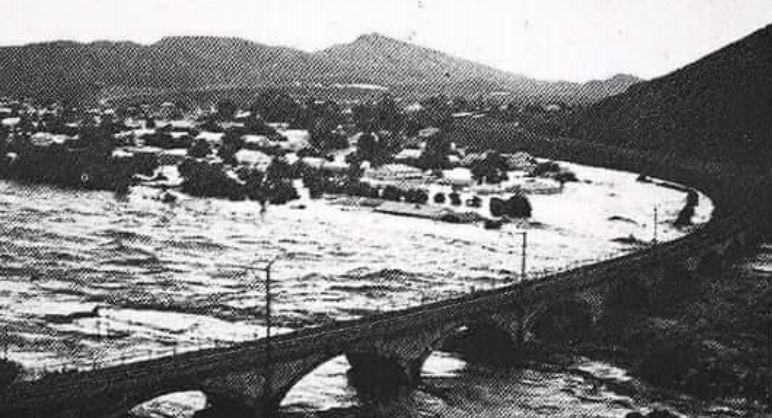

Press photograph of Laingsburg flood damage in 1981 (www.rsgplus.org)

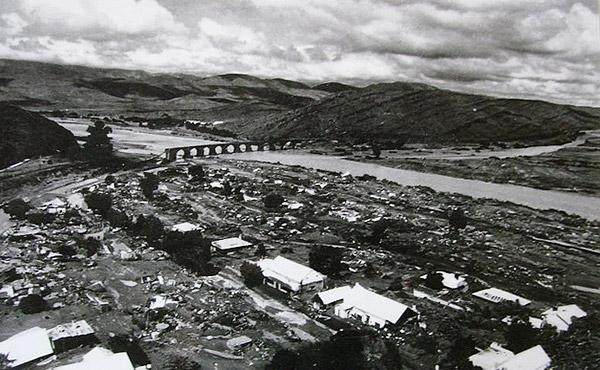

An almost apocalyptic scene of destruction unfolded as the river took away most of the town and only 21 buildings were left standing once the flood waters subsided. The sudden demolition of an old age home full of frail, defenceless people was truly unbelievable and one can hardly imagine their suffering. The town was not prepared at all and there was no evacuation plan. The Laingsburg flood of 1981 was rated as South Africa’s worst natural disaster at the time. What was also unprecedented was the scale of the national response, including establishing a Disaster Relief Fund and assistance provided on the ground from the South African Defence Force, and even from the SPCA (animals stranded in the flood) and farmers around the country provided fodder for stranded livestock. International organisations also responded (details in Pietersen 2018). All in all, the disaster caused R100 million in local damages. The disaster received unprecedented press coverage at the time and it is this press coverage that remains a key research source (Pietersen 2018).

Tourism and a fascination for tragedy

People have been fascinated by horrible death and unpleasant dying for many hundreds of years, and also by the odd and unusual, leading to the ‘cabinets of curiosities’ of the 1700s and 1800s, and ultimately to museums. Although potentially morbid, tourism now includes atrocity and genocide museums, and visits to battlefield sites and sites of disaster like Chernobyl are quite acceptable. This niche form of tourism is called Dark Tourism and involves visits to tragic sites or sites where deaths of historic significance have occurred. Visitors hope to learn something of history that allows them to be more thoughtful about the past. These forms of tourism began to expand in popularity and variety in the late 20th century, seemingly with huge potential for future tourism growth. Other growing dark tourism subsectors include Genocide Tourism, Thana Tourism, Grief Tourism and others. This form of niche tourism can even include Slum Tourism.

Pripyat with Chernobyl in the background (Wikipedia)

Dark Tourism and contentious offerings

It is not Dark Tourism that is often seen as contentious, but the way that it may be designed as an offering for contemporary mass tourism. While interest in places where the deadlier events of history happened has always existed, there has been a recent change in that Dark Tourism has become commercialised, using disaster and atrocity and other exceptional events as tourism assets. Academic critics of Dark Tourism find dark tourism alarming in the way it recognises atrocity and suffering as a form of cultural heritage, to be exploited as a tourism or heritage asset. It is also said that Dark Tourism packages past disaster and horror for tourist consumption – yet, commercial reasons can be an important reason for establishing such a museum or visitor site, as in the case of Laingsburg and its Flood Museum. There are other distortions in Dark Tourism (and in many other forms of tourism too), with, for example, the tourism offerings at Alcatraz accused of ‘Disneyfying’ a site of suffering and savagery. Alcatraz is one of San Francisco’s top tourist attractions with over a million people visiting each year (Baycity guide.com).

Visitors increasingly flock to sites that resonate with pain and memory, but rather than wanting to experience a freak show or a voyeuristic encounter with the events at a disturbing place, these ‘dark’ visits are often selected by tourists to lead them to a greater understanding of past events and perhaps even affirm national and personal identity, for example at war memorials and battle fields. Heritage specialists often become uncomfortable about these places of tragedy and human suffering being seen as ‘recreational landscapes’ and recent scandals include tourists taking ‘selfies’ at holocaust sites. Tourists do have to be gently reminded that they are at a site where thousands of people suffered and died, but in general, the more popular atrocity museums find that visitors must experience the site for themselves.

Mainstream Dark Tourism experiences around the world might include doing the tour of radioactive Pripyat near Chernobyl’s dead reactor four, or a thoughtful excursion to the Ground Zero 9/11 memorial in New York or popping in to see Alcatraz in the USA, or perhaps taking a long detour to Rwanda’s various genocide museums, some of which present a biased view of the atrocity, and serve political aims of the government in place.

New York 9/11 Memorial and Ground Zero (Wikipedia)

Some of these more unusual forms of tourism can provide spiritual experiences where “curiosity surrounding death, grief, and belief in spiritual residues, inspires visitors to sojourn to sites of profound personal sorrow or substantial tragedy, seeking intimate, tangible experiences with something significant, extreme, and perhaps psychologically if not physically dangerous” (Edwards, 2020). This type of tourism can also include ‘Spook house’ tours of ‘haunted’ mansions and castles in the USA. These are not random tourism offerings and are often carefully designed and market to attract ‘customers’.

A scary house in Hillbrow. Not yet on the tourist trail (The Heritage Portal)

Beware of the message at Atrocity Museums

Memorials and museums often have an agenda and can reflect the biases of the curators or of the regime that is funding them. Nothing is neutral in their museum displays and intentions, with, for example, Colonial collections in the UK and Europe coming under heavy fire for their acquisitions during times of colonisation and conquest. Visitors must be alert for one-sided claims to the authenticity of a place of atrocity and watch out for evidence of groups claiming that the site or event represents their sole interests. There can be a lot of white-washing in these types of museums or sites of atrocity as tourist destinations, with biased versions of the truth being presented. The Kigali National Genocide museum in Rwanda, for example, has met with the criticism of favouring the ruling regime.

Respectfulness in places of atrocity and the ethics of suffering

In designing an atrocity museum or designating a site of tragedy for memorialisation, it is important for the deaths to be ‘historic’ as the more recent these deaths and disasters are, the more painful and contentious the process of remembering and memorialising them becomes. For example, Atrocity Tourism may include visits to battlefield sites, medical museums, concentration camps and sites of disasters – but preferably those where the passage of time has worn away the screams of victims and washed away the blood on the walls, and you will have to imagine the whinnying of terrified horses and the clash of sword on sword because you won’t hear it for real. To visit any new site of atrocity or battle would be the preserve of war journalists and photographers, perhaps of United Nations peace-keepers, response teams and humanitarian workers. The media brings these places right into our living rooms, and there are also many ethical issues about how atrocity may be portrayed by photographs and how some war or tragedy photographs become iconic.

Perhaps sites must age and mellow before they can become tourism assets, ideally waiting for a few generations to pass, but also, the full truth needs to be known before they become formal sites for specialised and authentic tourism. The 9/11 Ground Zero museum was perhaps one of the most rapid atrocity museums in history.

Academic authors have explored the existence of an ‘ethics of remembering’ and acknowledge that landscapes of suffering often function as places of critical testimony for survivors, visitors and researchers, all with complex needs, perceptions, knowledge and responses. In particular, atrocity memorial sites must be developed as “safe spaces of listening, where stories about the place can be articulated and acknowledged by various stakeholders, while recognizing the moral complexities in representing violence through textual, visual and embodied means” (Till and Kuusisto-Arponen, 2015). This type of thoughtfulness must extend to all types of sites that seek to memorialise suffering.

Laingsburg’s horror described in tourism terms

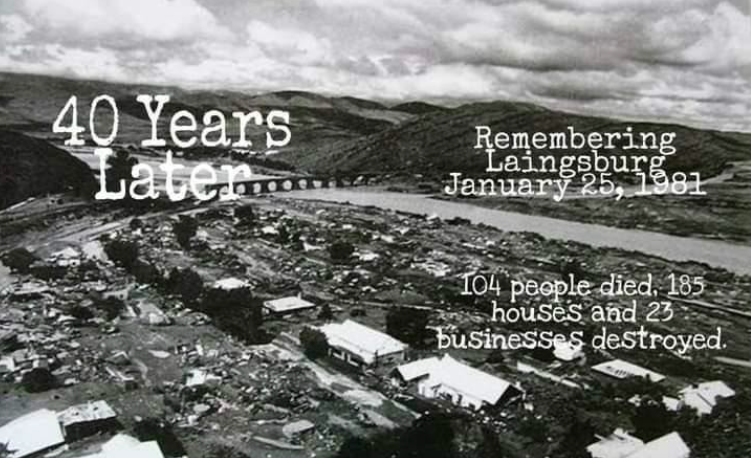

It is now 40 years since these floods. A good short account of the tragedy and the weather system that caused it is given here. Online tourism sites promoting Laingsburg describe the disaster in a brief and formulaic way, and the many online sites repeat the same information. We read over and over how the force of the flood waters was so immense that some of the victim’s bodies were washed all the way to the coast at Mossel Bay some 200 km away. And that in the days following the flood, the Floriskraal Dam downstream was dotted with the floating corpses of both humans and animals, drowned in the raging waters. All in all, we are told, the flood claimed 104 lives, with 72 bodies never recovered and buried under tons of mud. This information only scratches the surface of the tragedy. After the flood water subsided, the real battle for the survival of the town and recovery of its residents began, with damage to property and recovery costing R100 million. The dynamics of this recovery is what is really interesting and ‘museum-worthy’. My sense is that, with careful discussions with families of Laingsburg and without being disrespectful of the dead, much more could be made of the complex horror and survival story of the Laingsburg flood.

Contemporary press image of the Laingsburg floods and the railway bridge (Laingsburg Tourism)

Image of the 1981 flood aftermath, and looking towards the railway bridge. From Angelo Ricardo Hoorn’s reflective article 40 years after the floods and posted 25th January 2021.

The Flood Museum at Laingsburg

The 1981 flood disaster is one of the town’s key tourism assets, now represented by a Flood Museum near the Buffels River. The Laingsburg Flood Museum is dedicated to displaying the essence of the town and its people, and conveying the impact of the 1981 disaster. As well as stimulating tourism, the museum also aims to remember the residents who lost their lives in the 1981 flood. The town is on the major N1 north from Cape Town to Johannesburg and the municipality wanted to use its ‘disaster’ assets to lure visitors off the motorway. Yet, at the Laingsburg Flood Museum, the full suffering of marginalised persons in the town in the aftermath of the 1981 flood has not yet been represented, and a more inclusive and truthful memorialisation is needed.

The locality of the Flood Museum (shown by orange circle) next to the N1 motorway and the Buffel’s River (Google Earth image, 2021). The Old Age Home demolished by the flood was to the right of the museum prior to the 1981 flood.

The Flood Museum at Laingsburg (Google Street View)

Memorabilia, artefacts and information continue to be gathered for an accurate, up-to-date exhibition at the Laingsburg Flood Museum (SA-venues.com). Yet, the museum is rather conventional in ambience and there does not seem to be a strong attempt to ramp up the thrills to create a dramatic tourism experience that will have visitors aghast and telling their friends about this exciting, disturbing, fascinating story. The tragedy was in the days of no cell phones and the flood waters quickly took away both the electricity network and the telephone system. No-one could issue any warnings or call for help. This horror, now 40 years past, could become a ‘dark tourism’ offering.

The destruction of the Old Age Home and the valiant and spontaneous efforts of town residents to save the aged residents, deserve a detailed ‘dark’ display at the museum, even if this is horrifying and sad. In memory of this horror, one of the iron beds from the doomed Old Age Home, pulled out of the mud, could be displayed in the museum (if it was bigger and better resourced). This might be very powerful and poignant – or tasteless and grotesque. What in fact happened to all the beds, chairs, equipment, kitchen pots and pans, washed away from that Old Age Home? The collection and display of authentic artefacts is highly sensitive and it true that there is a delicate line between showing the shocking reality of ‘tragedy’ and shocking visitors so much that there is a public outcry and the museum is closed down. Displays must give a good visitor experience that is not unpleasantly disturbing for visitors or for groups with young children, and not offensive to the families of survivors of the flood tragedy. However, if the displays are toned down too much, they suffer from a certain lack of honesty and authenticity and may be seen too tame to visit. Despite the morbid nature of some artefacts, it would be essential to continue to collect and display authentic objects from the disaster and reflecting the different social, racial and faith groups in the town, and to encourage the donation and archiving of such items by the families of victims and survivors.

Forlorn leather shoes and water-damaged Bible from the disaster on display in the Flood Museum (Tripadvisor)

The complete narrative of a town swept away

The Master of Arts (History) thesis by Ashrick Pietersen (2018) is the defining study of the 1981 Laingsburg flood and provides much missing, unpleasant, controversial or ignored information, for example, of how ‘non-white’ (Coloured persons) flood survivors experienced the flood and how they recovered from the disaster without much support from other townsfolk. Pietersen (2018) notes that few official documents exist about the process of the town’s recovery and that the most useful source of information for historians today is the press, along with survivor testimonials.

Truth - the most valuable tourism asset

Visitors to the museum, especially foreign visitors, might make a special visit to learn more about how a racially-divided town struggled to cope after the flood. Scholars might be interested in comparisons between Laingsburg and New Orleans in terms of ignoring the safety of people of colour. The current Flood Museum only hints at the racial controversy and indeed, it would be a brave effort to begin to reflect on this rather hidden racial aspect of flood recovery in an apartheid-era town. All sorts of displays and information could tastefully and intelligently highlight a multi-textured tourism narrative, happening as it did in apartheid South Africa.

From a South African history perspective, it would be important for visitors (who now are from all population groups in South Africa, as well as international visitors) to learn more about how people lived with the injustices of apartheid planning in these small towns, and how the ‘non-whites’ were forced to live in the more vulnerable areas of town and about the land issues in the town. Also, of interest to Laingsburg visitors might be the different racial experiences of the flood, the difference in faith responses (Christian and Moslem) and the way that different families from different economic groups coped with the loss of their families and homes, and how people of the different races coped with starting again. There will be groups of people who do not come out well in this scenario, but also many stories of heroism. Many of the people who have knowledge of this event and aftermath are still in the town and are repositories of knowledge.

At the time of the flood disaster of 1981, there were unpleasant allegations at the time that Coloured victims of the flood had been buried in a mass grave. An archaeological investigation in 2003 proved conclusively that this had not happened. To take the process of reconciliation and healing in the Laingsburg community forward, the Provincial Government of the Western Cape requested the Municipal Council of Laingsburg to consider upgrading the former Coloured cemetery where eight Coloured victims of the flood were buried. There was also a commitment that these graves would receive the same recognition as the memorial cemetery where most of the [white] victims were buried. This belatedly went some way to acknowledging the Coloured townsfolk as valid victims of the tragedy. Also, a full revealing of the good and the bad of the 1981 disaster would be very useful for researchers, town leaders and policy makers to avoid a controversial situation in the future.

What do visitors think about the displays?

From internet sites commenting on the Flood Museum, most visitors found their experience satisfying, with both exhibits and the curator (a survivor of the floods) very informative. Tripadvisor noted travellers reporting that there was a good collection of flood artefacts and other memorabilia and that the lady manning the museum was a great asset. Others found their experience underwhelming. The displays seem tame, said some visitors, with many opportunities to share deeper information on this tragic event not taken up. One visitor mentioned that a wall-sized satellite image of the town, river and surrounding catchment would go far to create a more informative tourist experience. The most frequently asked question refers to where the nearest coffee shop or restaurant is in relation to the museum.

Disaster planning for future flood events in Laingsburg

In 2008 the Buffels River flooded and again in 2014 when the downstream Floriskraal Dam was filled to 150% of capacity, a worrying situation as the dam was not designed for this much water. Even in the 2014 flood, the disaster situation was complicated by the failure of telephone, cellphone and internet connections in Laingsburg because of the weather.

The current Laingsburg local municipal Integrated Development Plan (IDP) mentions nothing about floods as a major risk to the town and its farming surrounds, and does not provide details of how the flood disaster risk is to be mitigated, and what the evacuation and recovery process would be in another severe flood. South Africa is a signatory of the international Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030), and the South African National Disaster Framework of 2005 required that the municipal Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) must contain a disaster risk assessment and a disaster management plan for the municipality. The current Spatial Development Framework for the Laingsburg Local Municipality also does not mention the 1981, 2008 or 2014 floods as a form of ‘spatial’ risk, but, somewhat vaguely, does mention the idea of enforcing a 1:50 year flood line, i.e. no building within this designated area. In 2021, 40 years after the ‘big one’, there is still no protective infrastructure (levees, gabions, concrete walls) to divert or slow the river floodwaters, and it seems now urgent for landscape architects to design and deploy green infrastructure solutions to manage the river and create a safer urban environment. Or the town should be moved out of the flood plain.

Laingsburg (pop. 8 952) is a very troubled town, with political conflict, racism, endemic poverty and unemployment, problems with youth, alcoholism and high crime rates and municipal corruption. Yet, the 2020 Local Economic Development (LED) plan has many good ideas on how to create a more dynamic and successful Laingsburg, and interestingly does not refer to the flood as a tourism asset. Perhaps poverty and under-development are more important ‘tragedies’ than infrequent floods.

Research on the Buffels River catchment

There is a paucity of long term scientific research on the Buffels River catchment and its rainfall and flood patterns. A detailed study to document the January 1981 floods in the south Western Cape was undertaken by the Department of Water Affairs in 1983 (Kovaks 1983) and Zawada (1994) carried out a palaeoflood analysis of flood events prior to the current historical record. Such geological studies can investigate flood patterns of hundreds of thousands of years ago and help to determine the probability of future flood events. The Zawada (1994) study found that flood events of an 8000 m3/s water flow rate occurred up to 10 000 years ago and one must consider that this level of flow could return. The 1981 flood flow rate was a massive 6000 m3/s. With climate change and ocean warming, it is highly likely that the weather system that created the 1981 flood could intensify and a valid contemporary question is whether the Floriskraal Dam could withstand an 8000 m3/s flood event (Zawada 1994). If the Floriskraal Dam wall was to collapse, a massive amount of water would carry on through the mountains down to Mossel Bay, wiping out other small places along the way. Clearly some advanced planning and investment in flood infrastructure is needed to prepare for this threat, starting now.

The image below is of the Floriskraal dam, with vast ominous areas of sand deposited by many past flood events. The town is not visible in this image, but would be to the left. Amazingly, many survivors of the flood ended up in this dam and were rescued here. Many of the dead are still there, buried under metres of mud.

The Floriskraal Dam in 2021. There is a large amount of river sediment coming down into this dam from the many past flood events. There are also concerns that the dam wall might not hold in a flood event of 8000 m3/s (Google Earth image, 2021).

Although the Zawada (1994) study found that it would not be possible (with 1994 technology) to predict the return of floods or their magnitude, predictive technology has improved considerably over the last 40 years and climate modelling is now a major scientific activity around the world, particularly in the light of climate change. Disaster Risk Reduction and Disaster Management are also now major elements of research and international planning, so it should be easier to plan for and respond to disasters now, resulting in better outcomes. History need not repeat itself.

Main image: The Day after the 1981 flood via KarooSouthAfrica.com

Sue Taylor biography - Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (trash), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes and buildings. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- Edwards, ED. (2020). Morbid Curiosity, Popular Media, and Thanatourism. Australian Journal of Parapsychology. Dec 2020, Vol. 20 Issue 2, p113-138

- Kovács ZP (1983) Documentation of the January 1981 floods in the South Western Cape. Technical Report No. TR 116. Department of Water Affairs. Division of Hydrology.

- Pietersen A (2018). “There was simply too much water”: exploring the Laingsburg flood of 1981. Thesis (MA)--Stellenbosch University, 2018.

- Till KE and Kuusisto-Arponen A-K (2015). Towards responsible geographies of memory: complexities of place and the ethics of remembering. Erdkunde. Vol. 69 Issue 4, p291-306.

- Zawada PK. (1994). Paelaeoflood hydrology of the Buffels River, Laingsburg. South African Journal of Geology, 97(1).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.