Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the 1991 edition of Restorica, significant space was dedicated to the debate over the Civic Spine project. The overview of the controversy has already been published on The Heritage Portal (click here to view). In this piece, the voice of the architects is brought to the fore. Thank you to the University of Pretoria and the Heritage Association of South Africa for giving us permission to publish.

Historical background

The architects referred to several extracts from the book From Mining Camp to Metropolis by Gerhard-Mark van der Waal. These highlight aspects of the history of the Civic Spine and the various shortcomings which the author has noted, have been addressed by the project:

Of all the squares, Market Square presented the liveliest aspect- through the daily congregation of a mass of buyers and sellers and the visual cohesion of its components -but even this square failed to become a symbol with many references, because its only had a single function. Part of the explanation for this state of affairs probably lies in the fact that Johannesburg's raison d'etre lay outside the town· - in the mining area. There was in fact no ceremonial or social focus in the town itself. Market Square remained the most important city square. Originally established as a community centre, the square gradually saw its functions scaled down to those of an administrative and service area.

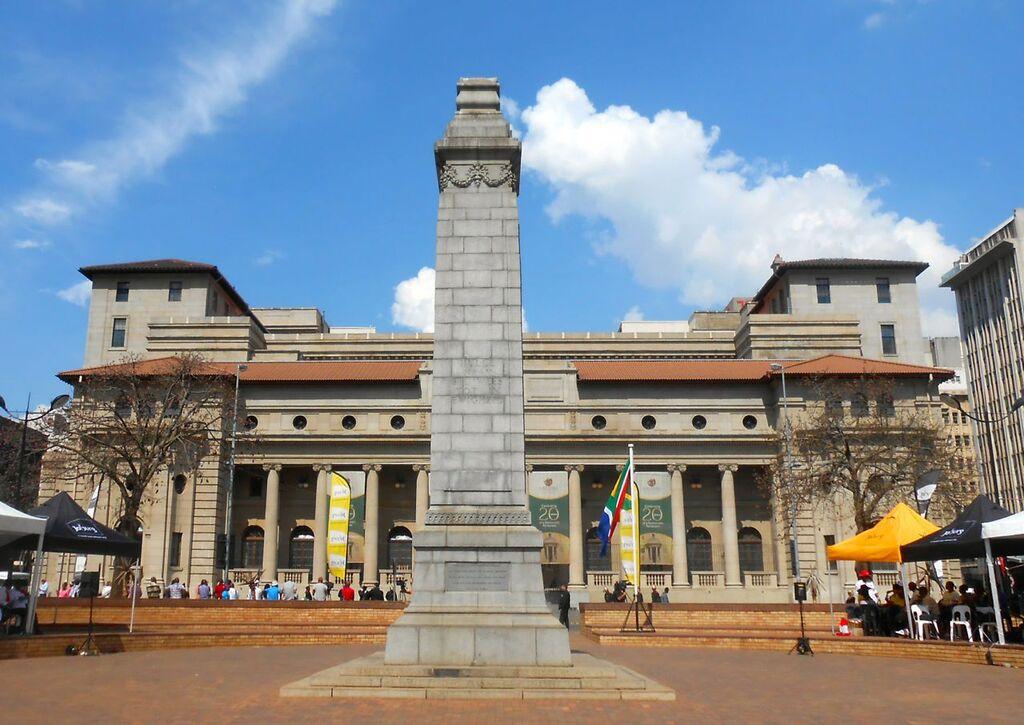

Until the early 1930's the single mass of the City Hall filled the eastern portion of the square, leaving only a narrow little street parallel to and west of Rissik Street. The row of plane trees on the sidewalk between this little street and Rissik Street failed to transform the space between the City Hall and the Rissik Street Post Office into a square. Until the Cenotaph was built in 1926 on the block west of the City Hall, there was nothing at all to fill the void (a lawn) on the western side- except a shelter for tramway passengers and the little building of the underground public toilets. But even the Cenotaph and the two new waiting rooms which were later built west of the Cenotaph in Simmonds Street failed to establish any visual link between the aloof posterior of the City Hall and the buildings on the northern, western and the greater part of the southern section of the square.

A more recent photo of the cenotaph (The Heritage Portal)

The winning entry in the design competition for the Cenotaph, organised in 1925, was submitted by J Lockwood-Hall, whose design showed many resemblances to that of the London Cenotaph (1920) by Edwin Lutyens. While it is very tall and beautifully finished, the Cenotaph fails to impress. It is not sturdy enough to form a visual bond between the City Hall and the Library, and it does not stand out well enough against its immediate environment to make a powetful statement. Any kind of screen, such as a fence or hedge of shrubs, would have structured the space around the Cenotaph and given it an identity of its own.

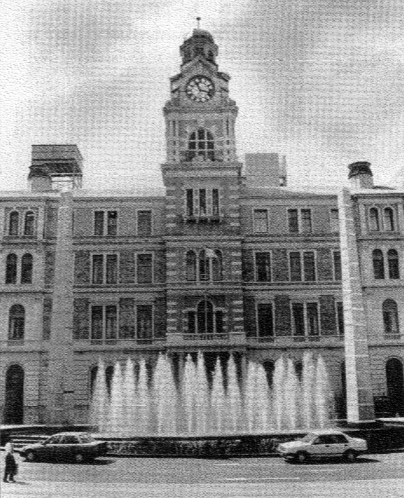

The fort-like aspect of the Library Building did not relate visually to the environment on either side or behind and, secondly, there was no relationship between the cultural function of the Library, the square in front or the surrounding buildings. To this day the Library, which should have had the capacity to stimulate cultural activities around it, has failed to exercise any noteworthy influence on the adjacent buildings.

An old photo of the Johannesburg Public Library (South African Builder)

Hardly any streets form a significant space in terms of visual diversity, cohesion or socio-cultural function. In these circumstances the community expresses itself in terms of individual interests rather than in unifying activities. Thus one searches in vain for a street that could be considered a genuine 'place' in the mining town. The character of the streets was determined by the buildings lining them: in themselves they had no form or space such as that created by islands and broad sidewalks with street furniture or trees.

While a tree-lined street is usually associated with an avenue, these trees were spaced too far apart to form dense foliage on either side of the roadway. At the same time, this spacing tended to discourage the social usage of the sideways. Indeed, the open spaces left by the building programmes of the previous period, were not regarded as social, economic or visual focal points within the community, but were reduced to the exclusive function of the buildings constructed there. The same applied to private sector buildings erected around the squares. Built to serve only the interests of the owners, they were focused on themselves, with no reference to their environment.

By their very height, the buildings put up around the square were, as enclosures of space and as providers of shelter for human activities, progressively divorced from the street as visual and human terrain. Indeed, there was a polarisation between the buildings as vertical visual statements and cores of activity and the streets as horizontal voids.

The rows of trees and flower beds on the lawns in front of the Library, which were divided in two by a paved walkway, never developed into a real park but rather served as formal entourage for the dominant Library Building. In any event, it was cut off from the tramway stops, lawns and paving around the Cenotaph by Simmonds Street with its heavy traffic.

The Civic Spine project arises from the Council's desire to acknowledge and enhance the historic elements and to create timeless places for people in the city. The Council appointed Gallagher Aspoas Poplak Senior to study the urban design potential of the city. They identified as the first action area the linear sequence of central city blocks extending from Sauer Street in the west to Eloff Street in the east and flanked by President and Market Streets. Traditionally, this part of the city has been the focus of historic events, civic functions and festive occasions and had the potential to become the symbolic heart of Johannesburg.

A concept plan was prepared by the Urban Planning Branch which explored broad ideas, one of which was to link the area through the use of particular street furniture, pacing patterns, tree planting and lighting, thereby making the Civic Spine distinct from the rest of the city.

Historic heart of Johannesburg that was the focus of the Civic Spine project (The Heritage Portal)

The design of the Civic Spine

Each section of the Spine has unique features while simultaneously constituting an integral part of the whole. An opportunity for a private/public partnership is created, and the chance for the owners of buildings along the Spine to make individual contributions to the scheme.

The first phase of the development focuses on the rim, that is the President and Market Street edges. Environmental improvement includes the redesign of the street space, the upgrading of pavements and signage and the planting of approximately 200 trees to form 'colonnades' which define the boundaries of the Civic Spine.

The city has established that over time there will be increased traffic within the area. Both President and Market Streets will have to cope with this. Our brief was to design within the increased number of traffic lanes required. The sidewalks are widened, creating increased opportunities for socialisation and activity. Trees, and vegetation, are planted at close intervals on both sides of the streets, creating a new avenue through which vehicles move, and a filter which protects the pedestrian and the spaces from the harsh impact of the traffic.

An increased awareness of the boundaries, the extent and content of the precinct as well as its civic identity, is thereby achieved. Traffic and information signs have been reduced to the required minimum, clearing the forest of posts that previously existed. All this provides the perimeter, the cohesion and definition of the elements and spaces within the precinct which provide the Civic Spine with its identity as a zone civic activity.

The Civic Square

The historic ceremonial heart of the city is the space between the City Hall and the Rissik Street Post Office. This square is expressed as the 'City room'. It is paved and has a major water feature symbolizing the Witwatersrand watershed. Traffic in Rissik Street continues to move through the square, on either side of the fountain. Two obelisks which rise from the fountain, frame the City Hall and Post Office entrances. The elements in the square were carefully proportioned to achieve this and the geometry of the square was studied in depth to locate the fountain in the most appropriate place. The square's levels and the paving patterns have been adjusted to suit the natural slope of the ground in such a way as to focus on the most important historic building in the city - the Rissik Street Post Office, originally the seat of Government of the Transvaal. The result is that the Civic Square embodies the dignity and formality of a memorable urban place.

The Civic Spine water feature

The Cenotaph and Library Gardens

The major impact in this part of the Spine has been the structures which form the perimeter of this area. The old ramps with their walls and railings which screened the view of the pedestrian and motorist from the space except for the trees, have been replaced by urban scaled garden structures to support a variety of planting. Two types of structure were used to give different effects of shelter and screening- a pergola structure which will be clothed with evergreen, flowering creepers and walls scaled to suit the robust Library building to be covered with the seasonal green, red and filigree of virginia creeper.

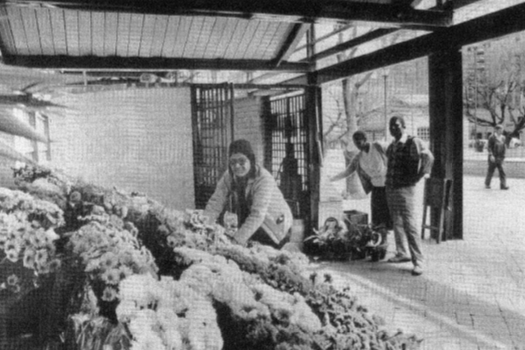

The Cenotaph is designed as a quiet green space where people may sit and contemplate. The pergola structures on either side provide the Cenotaph with a setting which has an appropriate scale. The central lawn and the wedge shaped paving provide for the natural diagonal movement of pedestrians and have a quiet centre appropriate to the reverence required for the Cenotaph. The flower seller and the charity book stall provide appropriate life and colour.

The Library Gardens space has been internalised for pedestrians and designed in such a way as to deflect pedestrian traffic into the area. It was decided to introduce a variety of uses to this space, in the form of small shops, stalls and eating places. Elements of these buildings reflect the architecture of the surrounding civic buildings in a modern idiom. These structures are accommodated on the other edges of the Library Gardens. As this space is subject to heavy traffic noise, high 'city walls' form the outer, or street facing blank facades of the shops, stalls and restaurants. In fact, the walls only run for one third of the space between the City Hall and the Library. The buildings also accommodate vehicular ramps to the underground parking garage, stairs, mechanical services and public toilets. The upper storey affords views over the gardens and surrounding area. The space in front of the Library is designed as an active people's place with restaurants, kiosks, water features, places to meet, to sit, to talk and enjoy the sunshine in the city.

Small shops and stall were introduced as part of the project

The Civic Spine project has strengthened the legibility of the precinct, enhancing the experience of those who move through it. The outer rim of trees has unified the discrete elements and spaces as a system of significant civic spaces. The spaces themselves have become more positively defined through the use of strong foci together with defined edges. Roads and pavements which were previously merely able to transport people, have become layered with opportunities for shelter and human interaction. Relationships between the inside and outside of spaces have been more defined. The character of the area is enhanced through the overlap of culture, meaning and idiosyncrasy in the expression of the architecture and the use to which it will be put while at the same time the treatment remains 'classical'.

The cost of the project and the legacy for the future

The entire cost of the project, President and Market Streets, the Civic Square and Cenotaph and Library Gardens which was given at R10,5 million, included all costs and fees. A very large proportion, some 45 percent of this cost, was used to upgrade and repair gas, water, sewer and stormwater services within the area. In addition the budget covered replacing the paving all of which would have been necessary within a few years according to reports of the Council. The remaining amount which was in fact spent on the Civic Spine is hardly significant in terms of the city's budget.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.