Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The Bergville area, in the foothills of the Drakensburg mountains, today the gateway into the Northern Drakensburg on Route 74 between Johannesburg and Durban, is steeped in history, so I should not have been surprised to discover its involvement in the World War of 1914 to 1918.

Bergville developed from a village founded in 1897, although its recorded history goes back 3,000 years to when the San first settled in the area. The first white man to record passing through was in 1837 (click here for more history and some fascinating personalities and a timeline).

Local historians no doubt have much more to say about Bergville’s past and the many encounters which took place in the neighbourhood. However, my interest is World War One and its military connection.

Not too long before the Great War of 1914-1918 broke out, during the Anglo-Boer or South African War of 1899-1902, one of the many blockhouses erected across the country, was to be located at Bergville. Today, it is the only known remaining blockhouse in KZN, and can apparently be found in the town’s courthouse grounds. While the 1899-1902 war took place on home ground, directly impacting the inhabitants, the war which erupted just over a decade later, although fought on foreign soil also had a direct impact on the community.

Bergville Blockhouse (Wiki Commons)

By August 1916, the Union of South Africa had been at war with Germany and its allies for two years. The Union had experienced a rebellion by a group of 11,472 white Afrikaners, had defeated the German forces in German South-West Africa (9 July 1915) and were sending white armed forces to Europe under Tim Lukin and to East Africa, initially to serve under Horace Smith-Dorrien but when he fell ill, under South Africa’s Jan Smuts (Samson, Britain, SA and the EA Campaign: The Union comes of age, reprint 2020). Crucially though, the armed white forces needed support behind the scenes and men of all South African population groups were employed in various capacities in the Army Service Corps, including transport and general labour, at home and abroad. This, however, was not enough and in 1916 more general labour was needed for service overseas – particularly from the black community.

Most men recruited to labour battalions were to join the Military Labour Bureau (MLB), notably the South African Native Labour Corps or SANLC to serve in Europe, of whom over 600 lost their lives when the SS Mendi was sunk on 21 February 1917.

SS Mendi (Wikipedia)

What is less well known is that 18,000 men served in East Africa as the East African Native Labour Corps (EANLC), of whom, at the time of writing, it is confirmed that 91 MLB personnel lie buried in today’s mainland Tanzania (then German East Africa), 9 in Kenya (then British East Africa), 1 in Malawi (Nyasaland) and 9 in Mozambique (Portuguese East Africa). Others are recorded in the CWGC South African Book of Remembrance, a total of 1,924 names of all population groups. These are of men who, as yet, have no known burial place.

Of those who served in the EANLC, according to the Death and Discharge registers of the contingent found at the SANDF Document Centre in Irene, some men had served in more than one theatre during the war – mainly GSWA but also Europe.

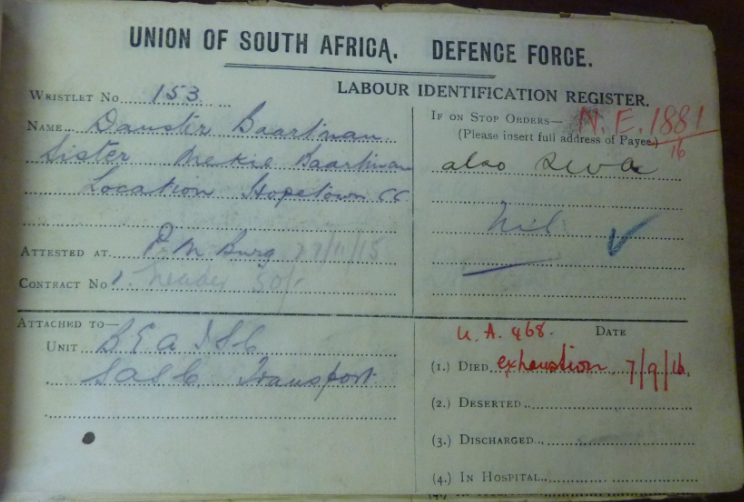

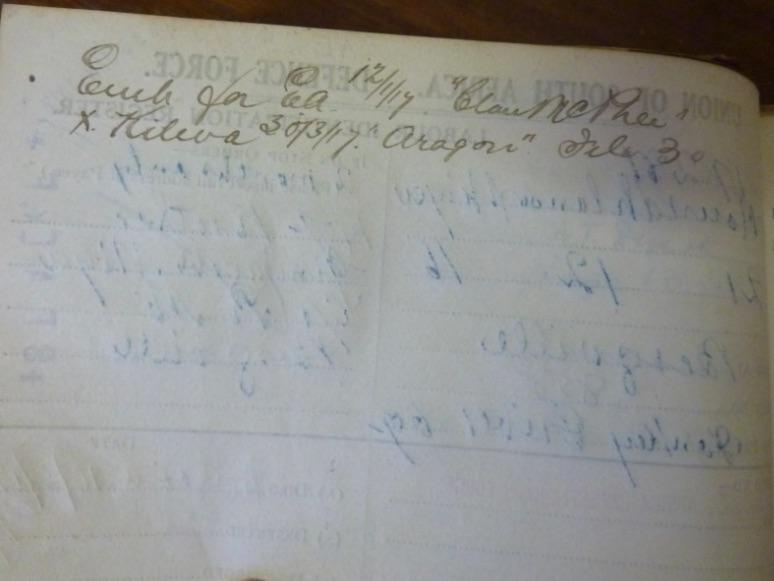

Death and Discharge records at the SANDF Doc Centre, Irene. D Baartman, EANLC 153, attested Pietermaritzburg, served South West Africa and East Africa, was SA Service Corps Transport, died 7 September 1916 from exhaustion.

However, it is from the October 2021 Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) consultation on a new memorial in Cape Town to recognise the contribution of those with no known grave that brought some new insights. A PDF attached as part of the consultation documentation contains the names and details of those to be remembered, extrapolated from the CWGC ‘Find War Dead’ database including what is generally regarded as ‘insignificant’ information. Bergville was a prominent mention being at the top of the list. Cradock, Encobo, Grahamstown and others feature just as prominently as one scrolls down.

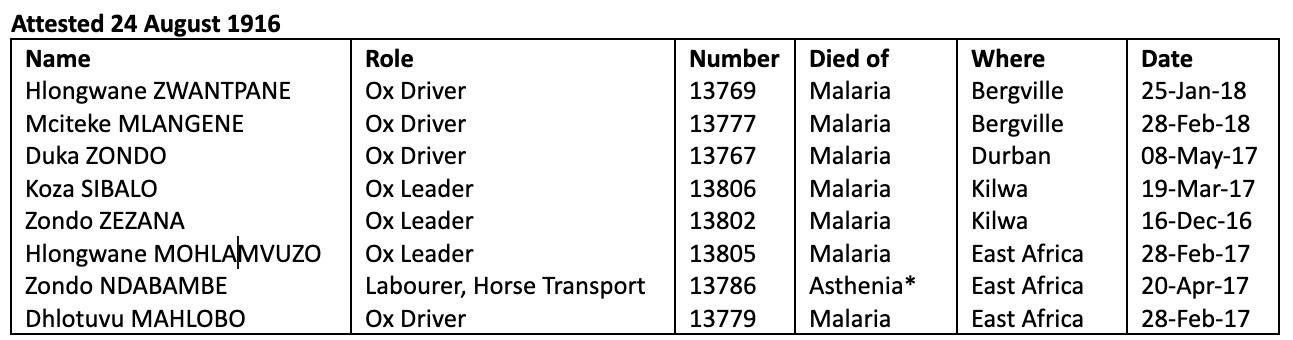

From this list, we are able to extrapolate that Bergville was an enlistment centre. Two contingents were recruited in the area, the first in August and the second in December 1916, the men forming part of the EANLC. We do not yet know complete numbers as data held at SANDF Document Centre needs further processing, but of those who enlisted at least 19 died. They are listed below. The dates of their death, and mention of SS Aragon, lead to a harrowing tale.

What led the men to enlist in Bergville?

At this stage, one can only surmise why a significant number of men enlisted in Bergville, given the generally accepted narrative that most labour recruits were coerced to some extent. Research in other parts of Africa where coercion and forced enlistment were said to occur, suggests it was more complex, some enlisted to earn money, others for adventure. No doubt, the reasons men enlisted in South Africa were for the same diverse reasons. It seems, that unlike places in the Eastern Cape, Bergville enlistees did so more willingly, despite the prevailing political climate caused by the 1906 Bambatha uprising and the 1913 Land Act which restricted black land ownership and residence. In contrast to the reports by Sol Plaatje in Native Life (1916), the development of nearby Rookdale as a black and coloured settlement area in 1915 seems to have had a positive effect in support of the war effort. There appeared to be cross-community collaboration.

Rookdale, within the 13 percent land allocation for non-white settlement in the Union, was bought in 1915 by twelve black and four coloured men for farming and settlement purposes. Under the guidance of a committee including South African Native National Council (now ANC) leader Josiah Gumede, Mr Applegreen and Mr du Plooy, land was set aside to meet government requirements and to allow community development. Further, at the start of the war, the SANNC favoured supporting the war effort hoping black South Africans would be granted more rights in the country. So, when recruitment started for overseas labour service, Bergville became an enlistment centre. (It would be wonderful if a researcher were able to undertake some oral history investigation amongst the community to see what recollections there are about ancestors serving in the war.)

Experience in East Africa and the SS Aragon

From Bergville, the men went to East Africa, the first contingent leaving on 2 September on the SS Hunstcliff or Glen Cunny, while the December contingent left in January 1917 on the SS Hunstcliff or Clan Macphee.

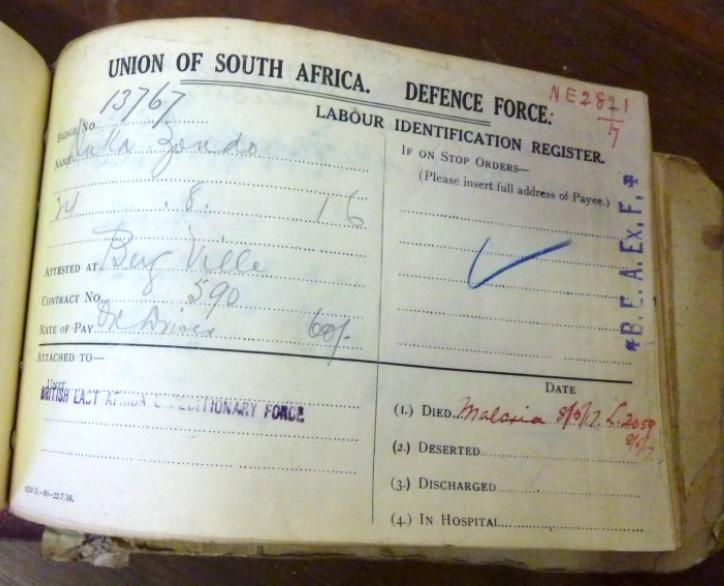

Death and Discharge Records (front and back), SANDF Doc Centre, Irene: Duka Zondo, EANLC No 13767, enlisted Bergville 24 August 1916, embarked on SS Huntscliffe on 2 September 1916 served EA Expeditionary Force as an Ox driver, returned 30 March 1917 to South Africa on SS Aragon, admitted to General Hospital No 3 in Durban on 4 May 1917, died of Malaria on 8 May 1917.

Once in East Africa, the men were allocated to different units, some staying in the dock areas, others being posted to base camps, while others joined the armed forces on the march.

The campaign in East Africa was gruelling – those who run the Comrades Marathon get some idea of the demands placed on the body thanks to founder of the run Victor Clapham who had served in East Africa for several months being discharged for reasons of ill health. He had 10 bouts of malaria in 586 days. Exploring the lives of individual soldiers who served in the campaign, a history of those who worked behind the scenes to keep the armed forces moving is slowly being compiled. It is a sad fact, that until recently the main focus of researchers has been on the fighting front rather than on those supporting the military endeavour, irrespective of their background. Invariably, as will be seen below, questions arise and it is hoped someone reading this will be able to add to the story.

While all suffered from the climate and long marches, carrying heavy loads, there were differences in diet and conditions which exacerbated the experiences of many, especially those undertaking carrier and labour services. It is estimated that 75 percent of all who served, were debilitated by disease or the effects of malnutrition. Those affected directly by war action (i.e. being shot etc.) accounted for 10 percent of losses. A Durban commander, John Hedley Kirkpatrick felt so strongly about the loss of men in 9 South African Infantry, he made an official complaint which was investigated.

By November 1916, Jan Smuts was sending white South Africans back to South Africa to recuperate from the effects of the campaign. Few were to return to East Africa, it being felt that the country was not suitable for white men to campaign in. This did not however prevent the second contingent of labour, recruited in December 1916, being sent in early 1917. However, by March 1917, the situation regarding black South Africans was as severe as what it had been for the white forces and it was decided to send 1,362 men back to the Union, including about 200 “Cape Boys”. On 30 March 1917, they embarked on the SS Aragon for a trip that was to last 17 days before arriving in Durban on 17 April that year.

However, the ship was delayed ten days in Kilwa Kisiwani harbour waiting for a convoy escort to undergo repairs. During these ten days, 74 men lost their lives. By the time the ship arrived in Durban, the number had increased to 129. Dr William Pike, Surgeon General, Army Medical Corps, who undertook an investigation into the medical conditions prevalent in the East Africa theatre, noted the following concerning the SS Aragon in his report.

- Two Medical Officers and eight orderlies had to be transferred at sea from another ship of the convoy to assist with the sick on the Aragon.

- The number of deaths on board was about the same in proportion as had occurred in 19 Stationary Hospital during the month of March.

- The health of Union natives generally may be considered as bad, because they are very liable to suffer from diseases which they have not met before, such as malaria, and, to a great extent, dysentery.

- The general condition of those on the Aragon was much below the average because:

1) They had been held up for a considerable time awaiting transport and an escort.

2) When this was provided they were embarked and then again delayed by the breakdown of the escort.

3) They were saturated with malaria and dysentery.

4) They were very depressed by the above delays.

According to the Senior Medical Officer, Kilwa:

In all cases the porters belonging to the Animal Transport were in a much worse condition than those of other units … The condition under which these porters were, during the rains, could not have been worse.

Many were old men, others young boys; at one time in the Animal Transport Camp there were two men each without a hand and many stated to me they had never been medically examined before leaving South Africa … I do not suppose there is one [Medical Officer] who speaks their language and the Controller of Union Labour was unable to give me any interpreters for the hospital…

Captain RDA Douglas, in Kisiwani recorded that between January and April 1917, he:

... had charge of the South African (Cape Boys) employed on Railway Construction work … Like the Seychelles porters they were not a strong body of men and were not physically fit to endure the trials of a tropical climate especially during the heavy summer rains … The Cape Boy has not the physique nor the stamina to battle with malaria … the knowledge of their soon returning to their homes and families, did not cheer them up. They became hopelessly depressed (probably accentuated by perpetual rains and misery of seeing a comrade die from fever) and a fair percentage died before they could be evacuated … A number of repatriated cases came down by rail to join the Aragon. Of these I detained 12 in Hospital deeming them unfit to travel. Of these 6 died at Kisiwani…

On 13 April, Dr John Miller, on board Aragon reported that the delay in Kilwa:

... had a very depressing effect on the natives, which affected adversely their general health. During the stay in Kilwa seventy-four deaths took place, 46 being from malaria, 27 from dysentery, and one native jumped overboard [13516 Bokkie Mayandu from Graaff Reinet]… The HMT Aragon sailed from Kilwa on 9 April and it was hoped that the sea voyage would have a beneficial effect on the health of the natives. It improved the health of those who were convalescent, but had a harmful effect on those who were in hospital.

Between 1 and 15 April 1917, there were 239 Military Labour Corps deaths, together with the 156 deaths recorded in March 1917 and 12 who died in British East Africa (Kenya). This suggests that of the 18,000 South African labourers who served in the theatre, 407 lost their lives (2.26 percent).

While the 600+ who drowned when SS Mendi was rammed on 21 February 1917 are given special recognition, the 135 who died on SS Aragon, remain in relative obscurity.

Ceremony commemorating the 99th Anniversary of the sinking of the Mendi (Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

White South African politicians stood for a moment’s silence when the news of SS Mendi was received in March 1917. However, it was the SS Aragon deaths that caused Prime Minister Louis Botha to order a formal enquiry into conditions of service and an end to labour recruiting for service overseas.

Botha wrote to Cape Politician JX Merriman on 27 April 1917: "However bad malaria might be in East Africa, I am unable to believe that the death rate amongst the Native labourers can be so much higher than amongst the European and Coloured troops, unless there is much that is lamentably lacking in the military arrangements for rationing and medical and hospital treatment” (in Grundlingh, p89). However. before the enquiry reported, no further labour men were sent to East Africa. The last contingent for Europe left in early 1918.

While only two of the Bergville enlistees died on the SS Aragon, the dates and causes of death, asthenia being physical weakness or mental and physical exhaustion, suggest the December 1916 contingent arrived and served in much harsher conditions than those of the first contingent.

The question remains, what caused so many men to effectively give up living, despite knowing they were on their way home? Conditions under which the men worked varied depending on where in the country they were, the type of work they did and who was in charge, as did diet. There are too many variables to suggest a common cause based on service. Was there some unknown underlying medical condition which was triggered?

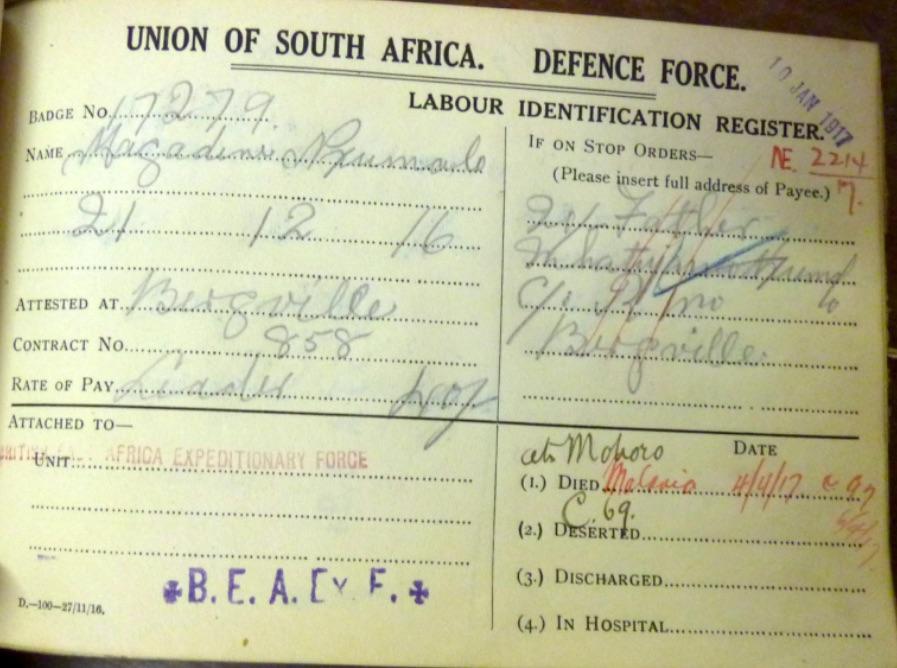

From the records held at the SANDF Doc Centre we can piece together a little more about some of the men from Bergville. Specifically, when they left, on what ship, what each person was to be paid and the terms of their contract. What has not been determined is the word at the top of the enlistment record of the men in the December 1916 contingent, while for the August intake, the word appears behind their name. So far, no duplicates have been found. What prompted the authorities to record this additional information?

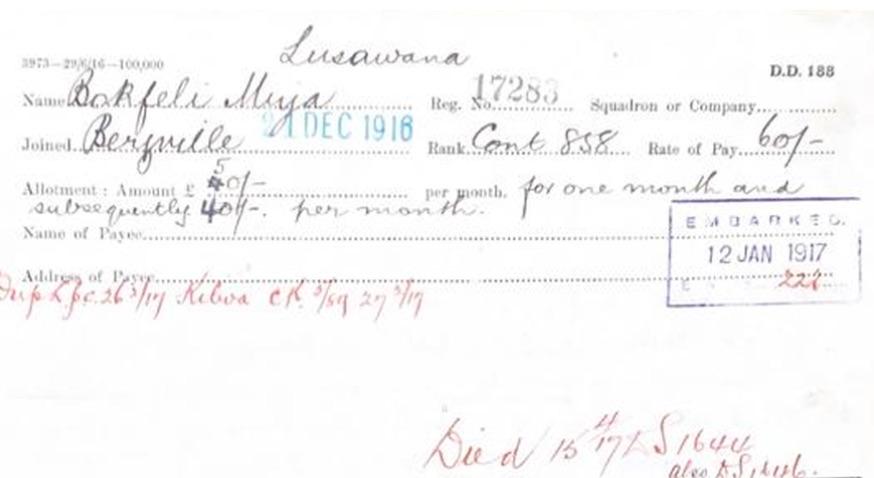

Death record SANDF Doc Centre, Irene: Bokfeli Miya, EANLC 17283 enlisted Bergville 21 December 1916, left East Africa from Kilwa on 29 March 1917, died 15 April 1917 on HMT Aragon. Note the name Lusawana above Miya.

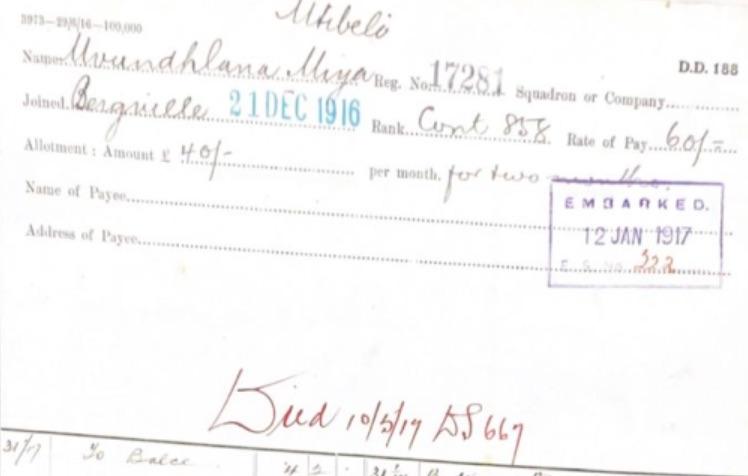

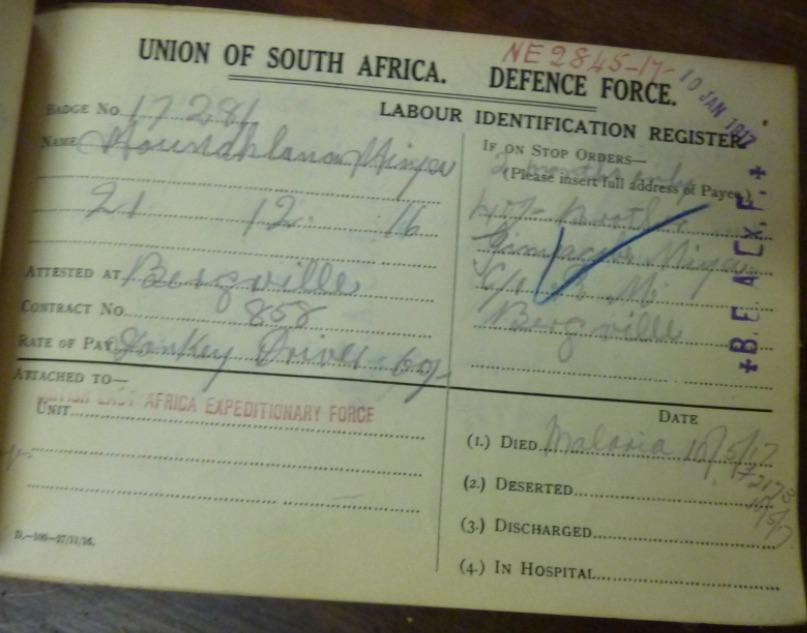

Death and Discharge records SANDF Doc Centre, Irene: Mvundhlana Minya, EANLC 17281, enlisted Bergville 21 December 1916, embarked for East Africa on Clan Macphee on 12 January 1917, left Kilwa on HMT Aragon 30 March 1917, died Durban 10 May 1917. Note the Mhbelo above Miya (the CWGC record shows Minya, this would have been confirmed with other records as sometimes errors were made in the field due to accent variations and interpretations of letter sounds).

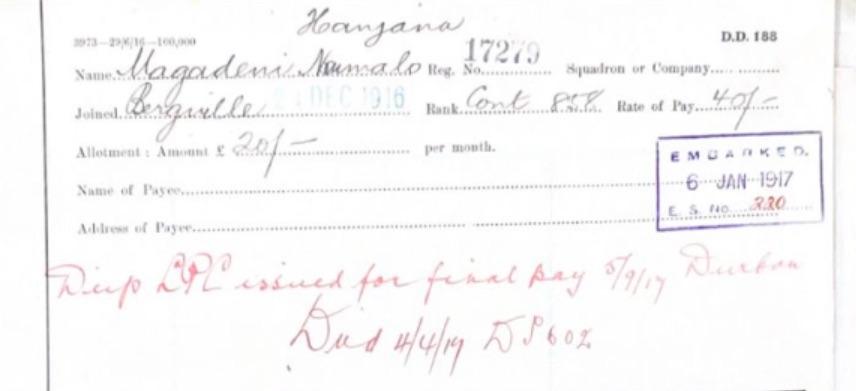

Death and Discharge records, SANDF Doc Centre, Irene. Magadeni Nxumalo, EANLC 17279, enlisted Bergville 21 December 1916. Died of Malaria on 4 April 1917 at Morhoro. Note Kanjana above Nxumalo.

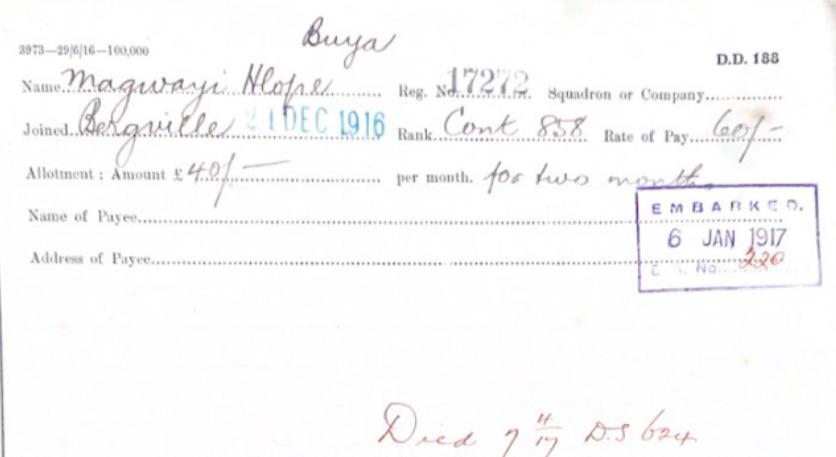

Death record SANDF Doc Centre, Irene. Magawayi Hlope, EANLC 17272, enlisted 21 December 1916 at Bergville, embarked for East Africa on 6 January 1917, died 8 April 1917 of Malaria at Kilwa. Note Buya above Hlope.

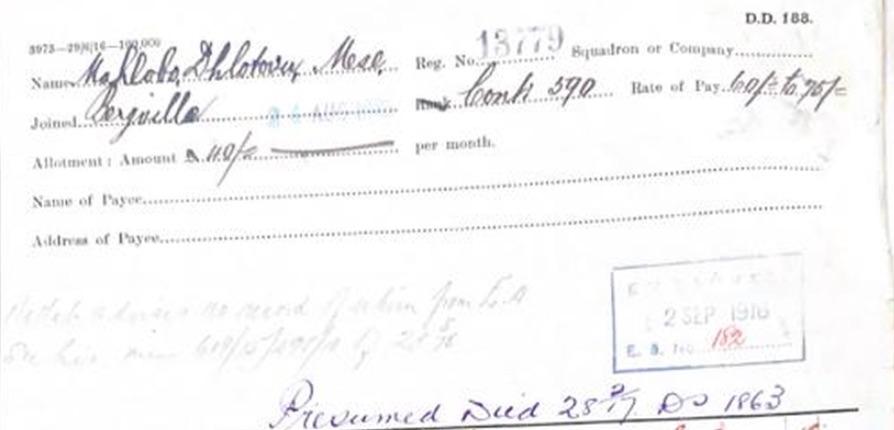

Death record SANDF Doc Centre, Irene. Dhlotuvu Mahlobo, EANLC 13779 enlisted 24 August 1916 at Bergville, embarked for East Africa 2 September 1916, (presumed) died on 28 February 1917 of Malaria. Note the Mese behind Dhlotuvu.

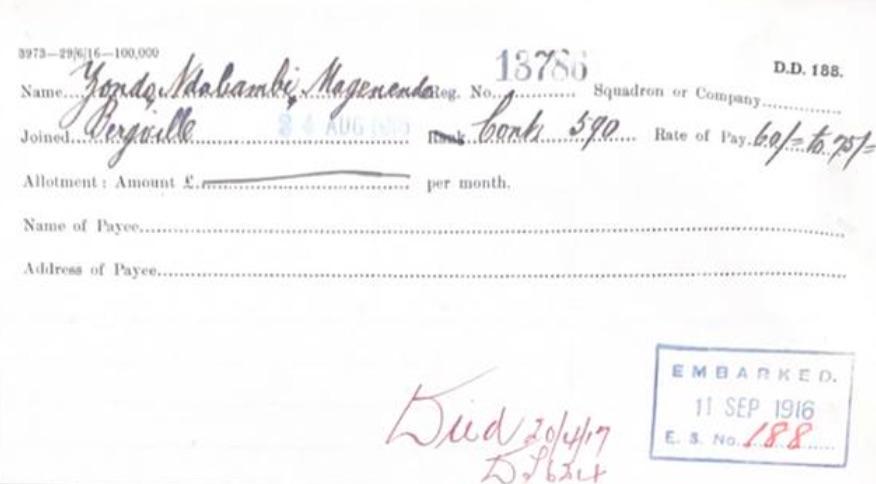

Death record SANDF Doc Centre, Irene. Zondo Ndabambe, EANLC 13786, enlisted Bergville on 24 August 1916, embarked for East Africa on 11 September 1916, died East Africa on 20 April 1917 of Asthenia. Note Magenendo behind Ndambambe (CWGC checks confirmed surname as Ndabambe, not Ndabambi as on document above).

Bergville was to see men from all population groups enlist. Again, full numbers are not yet known. However, from the CWGC ‘Find War Dead’ two white servicemen connected to Bergville who died in the war have been identified. Their records are also revealing: Wijnand (Victor) Hamman, enlisted on 1 May 1915 and died on 12 April 1917 in France. He served as 5898, with 2nd South African Infantry. He was the only white Afrikaner from Lichtenburg who served on the Western Front, and has two graves.

Bergville resident Sidney Stephen Ball, 16710, also of 2nd South African Infantry, was killed in action on 19 July 1918 in France, aged 21. “He was the son of Isabella W Ball of Bergville, Natal and the late Stephen Ambrose Ball. Native of Umhlumba, Weenen, Natal.” (CWGC)

Excluding the approximately 500 white South African women who served in a nursing capacity, the following is the population group breakdown of South African war service, and the total number of deaths:

- 145,897 white (armed and auxiliary services)

- 82,769 black (labour)

- 25,000 Coloured (armed and labour)

- 350 Indian (stretcher bearers included in Coloured numbers)

- 12,354 died on active service/Killed in Action (KIA)

The Bergville war dead are a miniscule number of the total (0.15%), yet their story, as with many – as yet – undocumented local histories, opens new windows onto one of South Africa’s defining periods of history: the war of 1914-1918.

Bergville is one of a number of locations on the South African World War 1 Heritage Tour which can be found at www.southafricaww1.com

Research into Bergville and other localities in KZN was part of a South Africa World War 1 project spearheaded by Professor Stefan Manz at Aston University, Birmingham, UK, in partnership with KZN Museum in Pietermaritzburg, funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council. It was informed by the CWGC Enquiry into the Non-commemorated.

About the author: Dr Anne Samson is an independent researcher and co-ordinator of the Great War in Africa Association (www.gweaa.com). She is author of two books on South African involvement in the East Africa Campaign and a biography on Lord Kitchener: The Man not the Myth (Helion, 2020).

Further Reading:

- Albert Grundlingh, Fighting their own war: South African Blacks and the First World War

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.