This is another of those books that is now a classic of early 20th century South Africa. Its age and rarity pushes up the price of the original book on the antiquarian auctions and hence expect to pay well over $200 for a first edition. Alternatively you may wish to settle for a reproduction from Amazon priced from $13.57 to $45. Or if you are a fan of online reading, take advantage of the free download available via UCLA or the Guttenberg project. The latter is an excellent option as the book and its many black and white photographic reproductions come up on your screen page by page.

William Scully (via Wikipedia)

However, as a book collector, I was delighted to acquire a first edition of the book. I enjoy the physical feel of the slightly yellowed thick pages. One quickly realises why this book has become a classic of Johannesburg and mining history. William Scully was an Irish born immigrant but lived in South Africa from the age of 12 and developed an intimate knowledge of the country as he travelled about on horseback, by Cape cart and later by rail. He endured hardships and revelled in adventures. His voice is one of authenticity and he has the firm views of a man who had personal experience of all he wrote about. Yes, there are prejudices but they are of his age and for his time he was a great humanitarian. He was a prolific writer, poet and multi-talented man whose life spanned the late 19th and early 20th century. Scully was a prospector of diamonds and gold (mainly unsuccessfully), an adventurer, a wanderer and a traveller during his younger years. He later opted for a life of greater stability and a regular income as a civil servant in the Cape. He ultimately made his living as a magistrate in the Eastern Cape and later in Springbokfontein in Namaqualand, Northern Cape. He was largely self-educated in the tradition of the autodidact.

He was a remarkable man in his early championing of the welfare of the oppressed, distressed and disadvantaged. He was unusual as he wrote about the living conditions of both African and Afrikaner dispossessed by war, the passing of the nomadic life of the trekboer and the impact of the Glen Grey Act. As a literary figure, Scully was unusual in that he wrote both novels, memoirs and travel books and even a history of South Africa. All his books are a source of information of life in South Africa between the 1870s and the 1940s. His writing reflects his sharp observation of daily living conditions. Subjects such a diet, income, health and criminality feature. He was an observer of and writer about human nature. Scully was a man with an enquiring mind, a curiosity about people whether white or black. He was not afraid to investigate official ineptitude or wrongdoing and expose it. Scully was the insider writing at the peak of his career with maturity and a lifetime of experience as a miner, traveller, hunter and botanist.

Scully was born in Ireland in 1855 and emigrated to South Africa with his parents in 1867. His father became a farmer so Scully’s formal education was fairly limited. Ill health when young also affected his upbringing. He left school early and by 1871, at the age of 16, he was in Kimberley prospecting for diamonds. According to the entry in the South African Dictionary of National Biography (SADNB) he shared a tent and mess arrangements with Frank, Herbert and Cecil Rhodes. In his memoirs he recalls his first impressions of Rhodes and gives a vignette of each of the three brothers. He clearly did not like Rhodes when they were both very young nor later when he met Rhodes at Groote Schuur, but though there was a mere two year age difference he says in his Kimberley years he was a boy and Rhodes was a man. By 1873 Scully was prospecting for gold in the Eastern Transvaal but with little success. Scully also studied botany and collected samples of local plants which he dispatched to universities and museums’ abroad.

It was as a writer of short stories, articles and poems and later as a traveller writer and author of two volumes of now classic memoirs that he achieved enduring fame. I was fascinated by The Ridge of White Waters and immediately went in search of Scully’s Reminiscences and then his Further Reminiscences - and these are all wonderfully readable accounts of a wandering life in 19th century South Africa. He was a keen observer of the contemporary scene.

Scully died in Natal in 1843. As Scully’s entry in the SADNB (volume 1, page 705) notes, his literary merit lay in the integrity with which he recorded the contemporary scene. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Ridge of White Waters. This book is both a travelogue and a memoir. The book opens with an account of travel from East London to Durban. The Durban of 1911 is so much more modern than the Durban Scully knew in the 1870s; Durban has trams, a new city hall, an impressive post office now acquired by the Union Government and the Durban Club. Rickshaw men fill the streets and Scully comments on their muscular legs but thin arms and the likely short lifespan.

Durban Town Hall

Scully then proceeds by ship to Lourenco Marques and he contrasts the old and new port. Civic administration, tariffs and the cost of living all come under review. He travels by train back into South Africa through the Lowveld and on to Pretoria. Government House was then described as one of Baker’s most lordly creations. Scully then moves on rapidly to the central theme of the book, the ridge of white waters, or the Witwatersrand with Johannesburg as its capital. He arrives by train at Park Station. His is a fascinating account of Johannesburg in 1911. The Rand Club he describes as “an immense stone pile, many stories high”, its interior, “a nightmare of superfluous ornamentation”, with soaring pillars of imitation porphyry. The Club is comfortable, somewhat inartistic and very expensive.

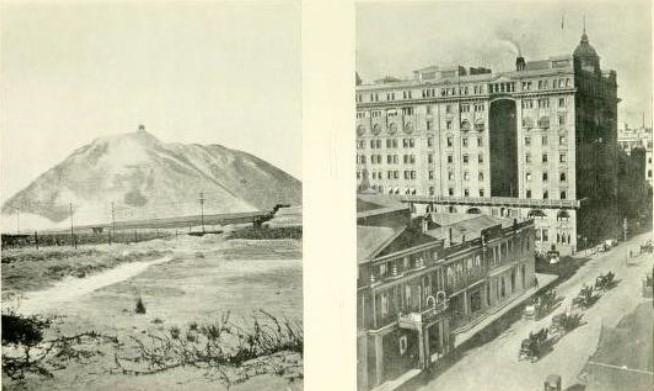

“From my room… I can look forth over intersection lines of streets, all filled with ceaseless and hurrying traffic. Away beyond the limits of the massed roofs the eye can just discern the outlines of dumps, smoke-stacks and wheel-crowned headgears”. The principal buildings of 1911 were the Corner House (new Edwardian era headquarters of the mining group of Wernher, Beit, Eckstein, Phillips and Company), the Standard Bank and the Stock Exchange. “...it is all a gloomy inferno of stone - a series of linked Babylon-towers of masonry heaped menacingly against the almost obliterated heavens."

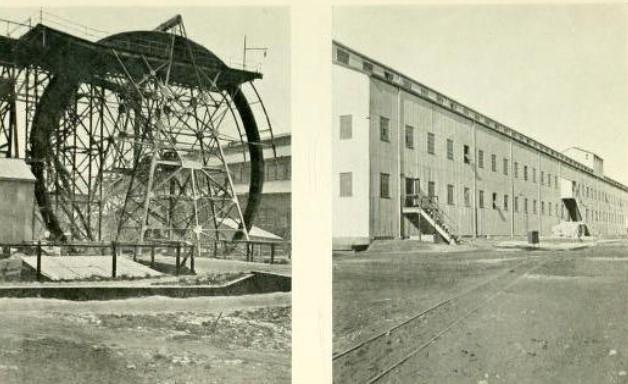

Kleinfontein Mine (left) and Corner House (right)

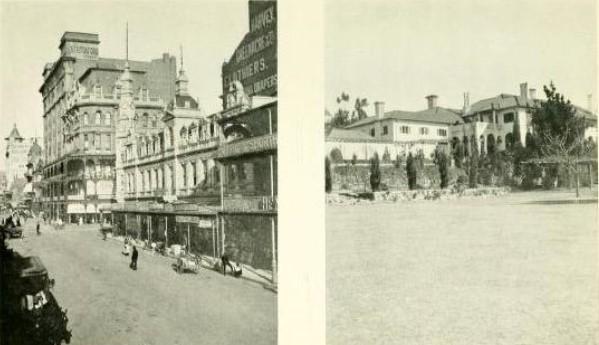

Johannesburg was a town of some size and sophistication in 1911; its population exceeded 180 000 in 1908. The town’s boundaries had been extended in concentric circles to encompass about 6 square miles. The town had achieved a measure of permanence that belied its mining camp origins. There were established schools, hospitals, churches, shopping emporiums, businesses, churches, banks, theatres, social clubs, sporting clubs and golf courses all adding to amenities for families. The mines with their ever growing mine dumps powered the economy of the town. But Johannesburg was no longer a mining camp or a mad chaotic place of prospectors and hopefuls where no one knew who would come out on top of the wealth stakes. By 1911 gold mining was organized on a group basis with an oligopolistic structure of large holding companies owning several mines. The town had moved on to permanence, a clearly residential class stratification shaping the suburbs. Townships and suburbs were opened up for private house construction according to wealth as capital gains were invested in property. The norm was to build bungalows, single storey dwellings for white owners who purchased plots for house and garden, achieving privacy and status whether in Kensington and Yeoville or Parktown and Forest Town. By 1911 there was a clear division between the mining areas to the south of the town, a central business and shopping area, with some residences interposed as apartment blocks, and to the north and north east the residential suburbs. Slums were evident in part of the town - in the Brickyards, Newtown, Doornfontein and Vrededorp. By 1911 the experiment to import Chinese labour was over - with repatriation completed by early 1910. Migrant African workers on the mines lived in compounds close to the shafts.

Pritchard Street (left) and Villa Arcadia (right)

What did Scully write about? For him Johannesburg had become a town of automobiles conveying large cigar smoking, mining magnates caricatured by D C Boonzaaier as Hoggenheimer or transporting a trio of silken wrapped ladies on a shopping spree. No two automobiles were the same. A tram journey took Scully to the top of the Parktown ridges to see the palaces built by the magnates with grand views to the Magaliesberg. In 1911 the Auckland Park car ran the visitor out to the Country Club, described as “the playground of the rich and leisured class”.

View over the Saxonwold Plantation from Parktown

Johannesburg Country Club

Scully tells us that Johannesburg’s wealthy and beautifully clad are people not born to the purple, luxury is new to them and so they are people who now have to live up to their wardrobes and their automobiles. Scully is filled with dismay at Johannesburg’s “abounding efflorescence of masonry“ and crowded skyscrapers. Our author now explicitly reveals his intense dislike of the Randlords, the barons of the nineties, who he sees having made their money from share speculations and who have now departed for London and the continent to spend their ill-gotten gains on town houses and mansions in Park Lane, country estates in the Home Counties and on grand art collections.

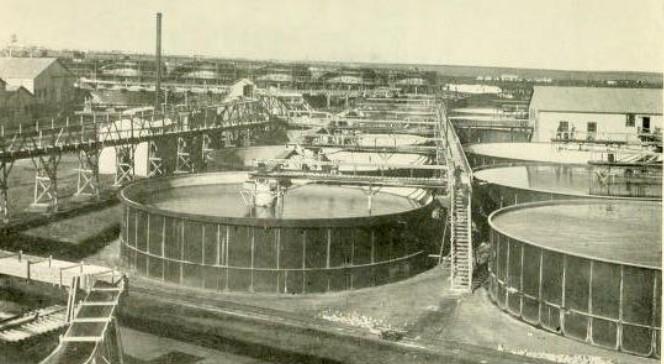

Travelogue is now abandoned and Scully switches to analytical mode and weighs in on gold mining investments citing examples of specific mines. He can’t resist expressing his opinion on the experiment of using Chinese labour versus black local labour, wages, fatalities, miners’ phthisis, mining regulations and the insecurity of work. It’s the social and economic conditions that turns Scully into the champion for the underdog and why this book becomes a rich seam for data and hard core information about mining and town conditions in 1911.

Cyanide Tanks Randfontein

Mining Infrastructure

I found Scully’s commentary or rather attack on the mining magnate absolutely fascinating. Had it not been for his precautionary measure of introducing pseudonyms for his Randlords with their palatial homes in Parktown and their offices in Commissioner Street, he might have been sued for libel. Like all good scandal it is as absorbing to read today as it was a century ago. Scully sees only six men as coming to own the wealth of the Rand, effectively through less than honest capital, financial and share transactions. He names his archetypical mining magnate as Mr Howard Lehmbek who lives on the Parktown ridge in a beautiful house and has a priceless collection of carved ivory including a crucifix stolen from the Vatican. I leave it to the reader to find a copy of Ridge of White Waters to speculate about who Scully was describing. His most scandalous description is on page 172.

Scully having impaled his Randlord, moves on to provide even more detail on Johannesburg and its development, its municipal organization, housing rentals and slums. Doornfontein in 1911 is described as “houses everywhere, houses mean, houses stately, and shops”. There are brief sketches of Jeppe Township and Judith Paarl. Vrededorp is a place of small cottages, crowded with children and increasingly owned by Asiatics (sic) displacing old Afrikaner settlers. There is a marvellous description of the criminals gallery in the museum of the police chief Mavrogordato and a glimpse of old Chinatown, the Chinese Club and the polyglot mix of races at the west end of the old town. Scully clearly has more sympathy for the slum dweller and shares with us his genuine curiosity about life in Fordsburg, life in a native compound, the illicit trade in liquor and the brothels of Johannesburg. Crown mines compound and hospital is described as the model as to how mine labour should be treated and managed. The final chapter leaves the reader with no doubt that Scully‘s political allegiances went to F H P Cresswell, leader of the Labour Party.

Overall, this is a curious book as it switches between travelogue, memoir, sociological analysis and political thundering. It leaves one with a curiosity about who Scully was. As mentioned, finding the Ridge of White Waters led me to pounce on his two volumes of memoirs. All three books, which I have now tackled in quick succession are worth the reading time to grasp the life of a man who cared about South Africa and its people. I read the two volumes of memoirs of Scully in the Guttenberg project so if anyone wants to dispose of any Scully books I am in the market.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.