Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

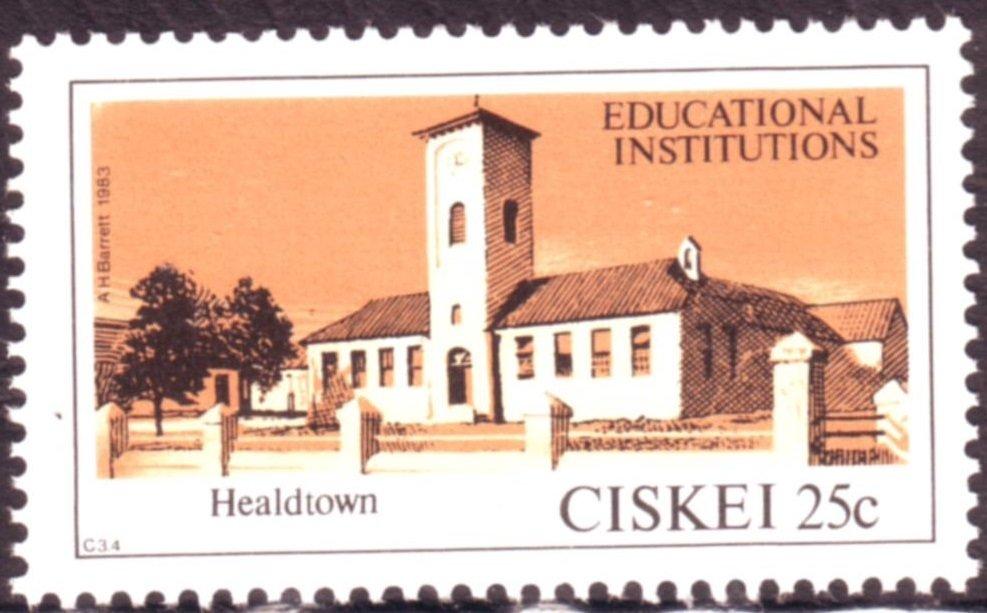

“Located at the end of a winding road overlooking a verdant valley, Healdtown was far more beautiful and impressive than Clarkebury. It was, at the time, the largest African school south of the equator, with more than a thousand learners, both male and female. Its gracefully ivory colonial buildings and tree-shaded courtyards gave it a feeling of a privileged academic oasis, which is exactly what it was.” Nelson Mandela - Long Walk to Freedom.

Book Cover

"In the soil of the Eastern Cape frontier lie many of the earliest roots of African nationalism in South Africa," writes Andre Odendaal in The Founders, a book about the founding of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the precursor to the African National Congress (ANC), in 1912. For most black South Africans, the process of colonization in the 19th century that led to the system of apartheid in the 20th century left them with a poor education, broken social and family structures and little hope of the life they wished for themselves and their children.

Book Cover

But there were pockets of excellence that offered black students an education at least comparable to that which their white counterparts were receiving. This was the education offered by mission schools. It was this holistic and quality education which empowered the early black leaders to articulate the call for an end to discrimination based upon race, and an equal franchise for all of South Africa’s citizens.

Men and women educated at mission schools pioneered the call for a better life for black South Africans. They were at the forefront for human rights for all of South Africa’s inhabitants. Mission schools were the doorway through which black South Africans were opened to the modern world of the early twentieth century. They provided a platform from which an educated class of black South Africans could realize the hypocrisy of the colonial system and forge a new African nationalism which was ultimately capable of felling British and Afrikaner hegemony in South Africa over a period of a century.

No other mission institute can claim to have made as significant a contribution in this respect than Healdtown Mission Institute. Lying low down below the valley at Ngwevu village, a settlement situated 15 kilometres east of the small rural town of Alice in the Eastern Cape, Healdtown is symbolic of the nexus of South African education history, representing much that has determined and influenced modern South Africa. It was founded in 1855 by John and Jane Ayliff, both Wesleyan ministers.

Healdtown from above (Google Maps)

Amongst the school's first students were individuals who would go on to play a significant role in the life of black South African society, more so in the political dimension. It is a process that ran concurrent with major historical events, from the school's inception in 1855 to the founding of the African National Congress (ANC) IN 1912, and leading up to the establishment of a post-colonial and post-apartheid South African state in 1994.

This is a register of all the students who went through the doors of Healdtown Mission Institute and went on to become principal figures in the struggle for human rights in South Africa:

Born on 11 January 1859, John Tengu Jabavu’s life spans many highlights. He received all of his formal education at Healdtown. After he matriculated in 1875, he went on to train as a teacher in Healdtown’s teacher training college and completed his studies in 1883. He went on to become a teacher at a high school in Somerset East in the Eastern Cape. He married another Healdtown student, Elda Sakuba, a daughter of the Reverend James Sakuba, one of the early black Methodist ministers. After six years of teaching he moved into journalism, and in 1896 he founded the country’s first black newspaper Imvo Tsabantsundu. In 1912, he was amongst the delegates at the founding of the African National Congress (ANC) in Bloemfontein.

John Tengo Jabavu

Meshack Pelem (1859-1936), another founder member of the ANC, left Healdtown after obtaining a first-class matric pass and a teacher’s certificate. He taught at primary school level before becoming the richest African in the Eastern Cape at the turn of the century.

Richard Msimang (1884-1933) was amongst the first black lawyers in South Africa. He completed his high schooling at Healdtown and received a scholarship to go and study law in England. He attended Queen’s College in London. On his return he played an instrumental role in the formation of the ANC and was responsible for formulating its constitution in 1919.

Ngaka Modiri Molema’s father had been a student before him. Molema started his schooling in his hometown of Mafeking (now renamed Mahikeng). He attended the Mafeking Stadt Wesleyan Mission School, where his musical talent gained him the London Tonic Sol-Fa College Junior Certificate. He then followed in his father’s footsteps by attending high school at Healdtown Mission Institute. He gained his matriculation at Healdtown and went on to train as a teacher at the nearby Lovedale Teacher Training College. It was at Lovedale, upon completion of the teacher's qualification, that he was nominated to travel abroad to further his studies. He went to Scotland where he chose to study medicine at the University of Glasgow. On his return from Scotland he went to settle back in Mafeking and became the first black medical doctor in his hometown. Influenced by what the Scottish had achieved in terms of preserving their heritage, he began a project to document the history of his people, the Barolong. He became one of the earliest members of the ANC in that part of South Africa, and co-authored its seminal document The Bantu Past and Present.

Ngaka Modiri Molema

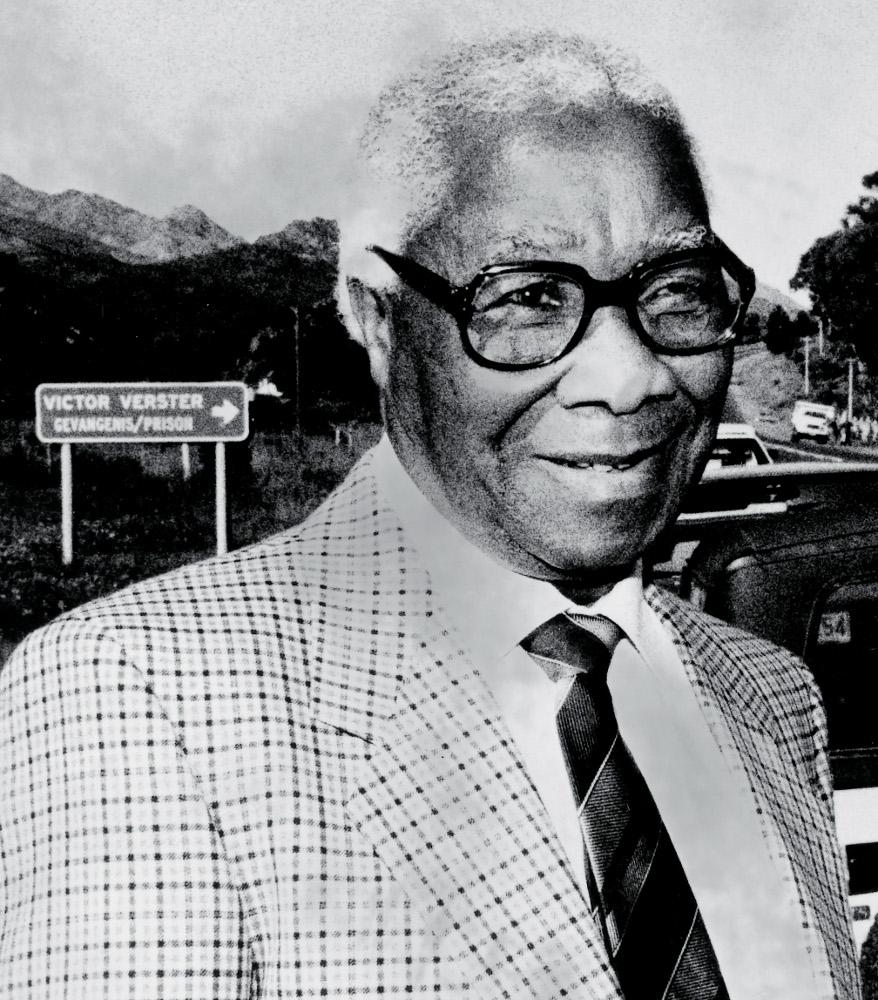

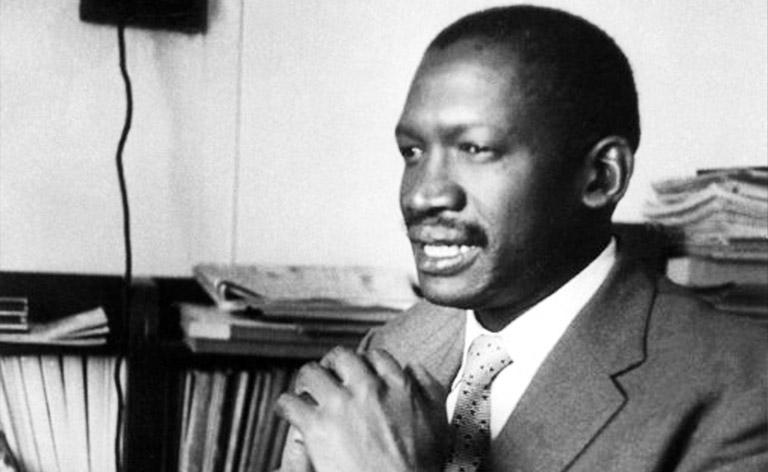

Dr Govan Mbeki (1910-2001). He is the father of Thabo Mbeki, South Africa's second democratically-elected state president. Oom Gov, as he was affectionately called, was a powerful voice in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. He first joined the South African Communist Party in 1946. He envisioned the struggle for equal rights in South Africa with the struggle for socialism. He actively advocated and campaigned for the fusion of closer relations between the ANC and the SACP. In 1964, together with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Wilton Mkwayi, Elias Motsoaledi, Ahmed Kathrada, Andrew Mlangeni, Dennis Goldberg and Raymond Mhlaba he was sentenced to life imprisonment at Robben Island in the trial famously known as the Rivonia Trial.

An experienced journalist, he wrote The Peasant’s Revolt, a study of peasant struggles in Pondoland and Sekhukhuneland, while incarcerated on Robben Island. He was released in 1987 and helped rebuild the structures of the ANC ahead of the organization`s unbanning in 1990.

Govan Mbeki

William Frederick Nkomo was born in 1915 in Makapanstad north of Pretoria. Dr William Frederick Nkomo Secondary School in Atteridgville, west of Pretoria, stands as a testament his contribution to South African society. He was a son of a Methodist minister. He began his secondary school education at St Peter’s in Rosettenville south of Johannesburg. He obtained his matriculation at Healdtown. After completing high school he enrolled for the certificate in teaching at Healdtown’s teacher training college. Armed with this he returned to Pretoria and founded an elementary school at Dougall Hill location. Because of forced removals the school was relocated to Atteridgeville township and renamed Dr VF Hofmeyer School.

He went on to further his studies at Wits University and qualified as a doctor. While at Wits he demonstrated leadership qualities and was elected to the university's Student Representative Council (SRC). He also represented Wits at the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS).

Wits Great Hall in Robert Sobukwe Block (The Heritage Portal)

In 1994, at the founding of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL), he was elected to the organization’s chairman position. In 1953 he attended a Moral Re-Armament Conference in Switzerland. The organization was a worldwide movement promoting peace. In 1966 he attended the Methodist Church’s World Ecumenical Council Conference in London. An outspoken activist for nonviolence, he acted as mediator between the government and the oppressed during a number of flash-point incidents, most significantly in the aftermath of the Sharpeville Massacre. In 1972 he was elected the president of the South African Institute for Race Relations (SAIRR). Shortly after his death in 1972, a school was built in Atteridgeville, and named Dr WF Nkomo Secondary School. In 2008, the Tshwane City Council changed the name of Pretoria's longest street from Church Street to Dr WF Nkomo.

William Frederick Nkomo

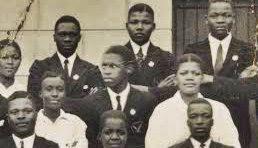

When a young Thembu royal first attended school at the ripe age of 15, little did anyone know that he would go on to change his country and the world. Since both his father, Chief Mpakanyiswa and his uncle, Chief Dalinyebo were committed Methodists, it was inevitable that a young Nelson Mandela would be sent to Chief Dalinyebo's alma mater - Clarkebury Mission School. Upon completion of his primary school education in 1936, he was sent to Healdtown Mission School thereby emulating other children of Thembu royal lineage who had been exclusively educated at Methodist mission schools. Mandela spent two years as a student at Healdtown.

Mandela's class photo at Healdtown

Intending to further his education and gain skills needed to become a privy councillor for the Thembu royal house, Mandela began his secondary education at Healdtown in 1936. Healdtown's headmaster during Mandela's time was the Rev Dr Arthur Wellington. The Rev Wellington was a staunch English patriot who liked to boast about his links to the Duke of Wellington, the British Army general who had defeated Napoleon at Waterloo.

In his second year at Healdtown Mandela took an interest in the two sports that he would hold dear to him for all his life, boxing and running. He also became a prefect. Night duty involved patrolling the front of his hostel to apprehend fellow boy pupils who, in typical school lads fashion, insisted on relieving themselves from the verandah, instead of visiting the outdoor toilet.

The housemaster in his hostel was the Reverend Seth Mokitimi. He impressed Mandela by standing up to Dr Wellington. This made the impression on Mandela that a black man did not have to defer automatically to a white man, however senior he was.

According to his own records, Mandela's most memorable experience at Healdtown was during one morning assembly in the dining hall. At each morning assembly, Dr Wellington made a grand entrance through Wellington's door, so-known because no one ever walked through that door except for Dr Wellington.

One morning, however, a black man draped in leopard skin and clutching two spears led the way forward with Dr Wellington following. He was the famous Xhosa poet S.E.K Mqhayi, whose writing was a major source of inspiration for early African nationalists.

Mandela said that when Mqhayi stood up to speak he was not particularly impressed. He said that apart from his traditional garb he was very much ordinary-looking. However, he said that he could hardly believe his ears when, in the presence of Dr Wellington and other white staff members, Mqhayi spoke of blacks having succumbed to the false gods of the white man for too long. He said that Mqhayi's performance was like a comet streaking across a night sky, and it made him begin to re-examine his views on colonial rule. Mandela went on to become a leading political figure in South Africa, whose 27-year imprisonment epitomized the resistance by blacks to oppression by the apartheid government. He was released from prison in 1990, and went on to become South Africa’s first democratically-elected president in 1994. He is justifiably credited with having saved South Africa from a cataclysm in the process of political change by his advocacy of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Mandela statue at the Union Buildings (The Heritage Portal)

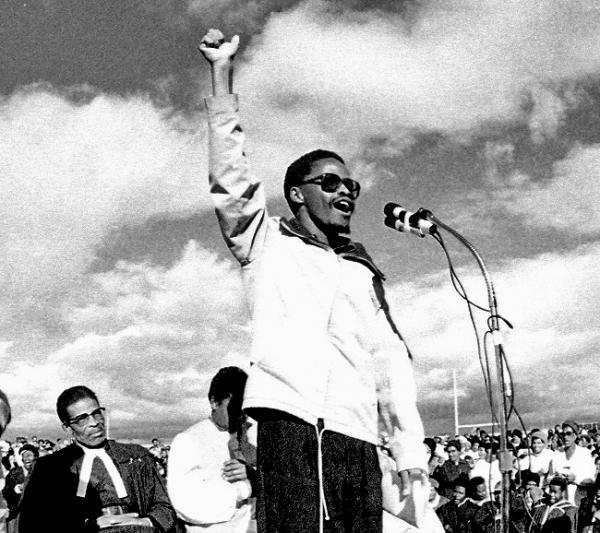

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe's relationship with his alma mater was to extend far beyond his days as a student at Healdtown. He was born on 5 December 1924, in the picturesque Karoo town of Graaff-Reinet, in the Eastern Cape. He was the last of Hubert and Angelinah Sobukwe’s six children. Hubert worked as a tradesman for the local city council, and his wife tended to the homestead and the children.

The only formal schooling offered in Graaff-Reinet’s location was provided by the Methodist church. This is where, in 1939, Sobukwe and his brother Charles obtained their first-class junior certificates. They passed with exceptional results, surpassing their seventy other classmates.

The Sobukwe family’s Methodist adherence made it natural for him to continue his schooling at Healdtown Mission Institute even though it was some 225 kilometres from home. Sobukwe arrived at Healdtown at the beginning of the school year in 1940. He enrolled for the NPL, the "Native Primary Lower", a three-year course which would enable him to qualify as a primary school teacher. As a newcomer, Sobukwe went into a wooden-floored dormitory of forty beds lined up along each side with a small locker in between each one.

His early days at Healdtown were marked by his love of English literature and tennis. He was an ardent reader and devoured all that he could lay his hands on. He revered the works of 19th century European novelists and particularly the Scarlet Pimpernel novels by Baroness Orcy and the Saint Stories by Leslie Charteris.

It was at the start of his second year that one of the most enduring friendships of his life began. Dennis Siwisa was a classmate to Sobukwe and shared a desk with him in their first year. He would later become a journalist. In How Can Man Die Better, the biography of Robert Sobukwe written by Benjamin Pogrund, Siwisa states: "My earliest memories of Robert Sobukwe at Healdtown are that of a happy and contented person. He was not given to speaking about his future hopes. His conversations were largely centered around his favorite sport (tennis) and girls like most boys of his age. He was, however, known to his fellow students for his brilliance and for his command of the English language. He invariably carried a library book with him, and went through two or three novels a week."

Sobukwe himself would later say of his early days at Healdtown: “I was introduced to English literature at a very early age by my eldest brothers who had a good library. I was also fortunate in the teachers I had. But especially at Healdtown. There was Miss Scott who encouraged my reading. It was a love for literature, especially poetry and drama."

His academic excellence was drawing increasing interest from his teachers - not only Miss Scott but also Hamish Noble, his carpentry teacher and boarding master, and the principal and his wife, George and Helen Caley. He was picked by his fellow students to become Head Boy. As expected, at the end of his three year stay at Healdtown he obtained a first-class pass, enabling him to go onto university. He enrolled at the University College of Fort Hare (known today as the University of Fort Hare) for a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree. He received a loan bursary from the Native Trust Fund, and his living expenses were taken care of by his older brother Ernest, and when necessary Hamish Noble and the Caleys.

The understanding between Sobukwe and his Healdtown benefactors was that, upon completion of his degree at Fort Hare, he would return to Healdtown to take up a teaching post there. As fate would have it, it was at Fort Hare that his involvement in politics began to take root and thus he never returned to take up a teaching post as envisaged by principal Caley. Still, he had left such a strong reputation at the school that Reverend Stanley Pitts, who became headmaster five years after Sobukwe had passed through Healdtown, remarked, "He was the brightest student we ever had."

Robert Sobukwe

Raymond Mhlaba (1920-2005) left Healdtown prematurely due to health reasons. His important role in South Africa’s political landscape started with the 1952 Defiance Campaign. In 1962 he became a commander of the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). Together with his seven co-accused he was sentenced to life in prison for his political activities in what became known as the Rivonia Trial. Upon his release in 1990, he formed part of the negotiating team which negotiated with the Nationalist Party for a democratic dispensation in South Africa. In 1995, he was elected to the ANC’s National Executive Committee and appointed as Premier of the Eastern Cape. In 1997 he was appointed South Africa’s ambassador to Uganda. In 1999 he was awarded the ANC's highest honour, the Isithwalandwe.

A contemporary of Robert Sobukwe at Healdtown, John Nyathi Pokela was born on 21 September 1921 in Hershel, near the border of Lesotho. He completed his high school education at Healdtown and in 1949 graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in Higher Education from the University of Fort Hare. He became a teacher but was expelled for his political activities. A member of the ANC Youth League, in 1959 he joined his schoolmate Sobukwe and other pan-Africanists in the ANC and formed the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). In 1982 he went into exile in Lesotho, and held the PAC`s chairmanship from 1983-1986.

Elijah Barayi was born in 1930 in Port Alfred in the Eastern Cape. He matriculated from Healdtown in 1951. In 1982 he became vice-president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). In 1985 he was elected the first president of the worker organisation conglomeration Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu).

Phyllis Ntatala was born on 7 January 1920 at Gqubeni along the bends of the Nqabarha River in Dutywa in the Eastern Cape. She spent most of her high school years at Healdtown but matriculated at Lovedale Mission Institute. She met the educationist Professor AC Jordan (the first black professor at the University of Cape Town) in 1938. They got married in 1940. The family went into exile in the United States in 1960 where Phyllis helped to spread awareness on the plight of black people in South Africa. Her son, Pallo Jordan, a political activist himself, was to later spearhead the formation of the Historic Schools Restoration Project (HRSP) during his tenure as South Africa’s Minister of Arts and Culture in 2008.

Phyllis Ntatala

Victoria Nonyamezelo Mxenge (1942-1985). Together with her husband Griffiths, Mxenge was robbed of a blossoming life and career by apartheid hitmen in 1985. After her matriculation at Healdtown, she met and married Griffiths Mxenge in 1964. Both lawyers, they became a prominent couple in the anti-apartheid struggle resulting in Griffiths being incarcerated on Robben Island alongside other political prisoners. He was murdered in 1981 by the state security apparatus. Victoria continued with the law practice that she and her husband had opened. She set up a bursary fund in memory of her slain husband.

In 1985, after rendering a speech at the funeral of the Cradock Four, she herself was gunned down in front of her two children by apartheid hitmen as she arrived at her Umlazi home. In 2006, she was posthumously honoured by the South African government and awarded the Order of Luthuli for her contribution to the anti-apartheid struggle and the field of of law.

Victoria Nonyamezelo Mxenge

Matthew Goniwe (1947-1985) spent his childhood in the Emaqgubeni section of the old Cradock, Eastern Cape township. He was the youngest of eight children. His parents, David and Elizabeth Goniwe, were farm labourers. He started his primary schooling at St James Primary School in 1953. In 1958, he joined the African National Congress. From 1964 until 1965, he completed his matriculation at Healdtown and became a member of the Moral Regeneration Movement (an organisation aimed at instilling morality amongst young people) and of the Healdtown Church Choir. Goniwe went to further his studies at Fort Hare University where he obtained a teaching diploma, majoring in mathematics, education, physics, and chemistry. Between 1972 and 1975 he taught maths and physics first at Cradock Bantu Secondary before moving onto Sithebe Secondary School, and finally Holomisa School at Mqanduli in Bityi Village, Eastern Cape.

Matthew Goniwe

Then began a period of political activism that would lead him to prison on countless occasions starting after the 1976 Soweto student uprising. On 27 June 1985, Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlawuli, who were later known as The Cradock Four, went to Port Elizabeth to attend a provincial meeting of the United Democratic Front (UDF) with Goniwe's vehicle. They were abducted by the apartheid security police near Bluewater Bay shortly after their departure from Port Elizabeth, and were then murdered by the security police.

Cradock Four Memorial (The Heritage Memorial)

In conclusion, on the occasion of the centenary of Healdtown in 1955, past student Ngaka Modiri Molema (1891-1965) wrote an ode titled Oh Healdtown. It illustrates his view that life without Healdtown was akin to being in "darkness" and that being at Healdtown transformed that darkness into light, conscientising those who became students with armour to take on, and eventually defeat the forces of discrimination in South Africa. It reads:

Looking on thee full flashes the light of years,

When thy present peace was pain, pain and pandemonium,

Of frenzied thirst vengeance, blood and spoil,

When veinly strove the assegai against both shot and shell,

When ruled chaotic darkness, and me thought might was right,

And selfish pride and prejudice obscured the light of heaven,

Though cradle in dire distress and nurtured convulsion,

A hundred years have rolled into time's bottomless ocean,

Years heralded by rapid war, and blood and tears,

But years aloof blessed love and devotion and sacrifice,

A century of patient, silent work and steadfast prayer towards final victory.

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg. After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue. On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa. Click here to see more of his work.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.