Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Tracey's Folly is one of Johannesburg's great historic mansions. In the article below, jounalist Lucille Davie unpacks the history of the magnificent property. The piece was originally published on the City of Joburg's website on 7 January 2010. Click here to view more of Davie's work. Main image via Yeudakn on Wikicommons.

Percival Tracey always got home in his car, but not in the usual way.

“Inevitably the car often broke down and Tracey, sitting behind the wheel, would complete the journey inspanned to a team of oxen. His family called the enterprise ‘Tracey’s Folly’,” records Nigel Helme in Thomas Major Cullinan: a biography.

Tracey was driving home to his 40-room, three-storey house in Mountain View. The mansion was completed in 1907, and Tracey moved in with his family. It was the only house on the rocky ridge, its sparkling white Cape Dutch gables, tall brick chimneys, and long wraparound veranda visible from miles around.

Visible for miles around (The Heritage Portal)

Tracey was a mining magnate, and his mansion compared admirably with other Randlords’ splendid homes - Northwards, Dolobran, Arcadia, among others in Parktown.

Northwards (The Heritage Portal)

Dolobran (Lucille Davie)

Villa Arcadia (The Heritage Portal)

Tracey lived in the house for only two years before he died. He must have enjoyed those short years. The large, double-volume entrance hall is panelled with Burmese teak, and contains two 300-year-old carved oak columns, a minstrel gallery, an inglenook (a fireplace nook) and a grand wooden staircase. Halfway up the staircase is a striking window.

Moving into the grand entrance hall with magnificent staircase (Lucille Davie)

“The Tracey family arms and motto Honores Ambire – Surround with Honour – are preserved on a cathedral glass (textured glass) window,” writes Alkis Doucakis in In the footsteps of Gandhi.

Almost every room boasts a fireplace, often with decorative Victorian tiles and elaborate wooden mantelpieces. Floors, doors and window frames are in rich Oregon pine. Door handles and light switches are in unique brass styles, now irreplaceable.

The exterior brickwork is superb, with craftsmanship that is no longer available in this country. Jointing is evident – where plaster between bricks protrudes – and was done to prevent moisture accumulating in the spaces between bricks. Exterior piping is made of caste iron, with brass bolts – it will never rust, and will be there forever.

Fifth owner

The Tracey family occupied the house until 1917, whereafter the Park Town School took over the building for the next 40 years, using it as a boarding house and school. In 1959 AECI bought the property, and used it as a training school and guest house. The house was sold to interior decorator Dorothy Van’t Riet in 1999.

Old photo of pupils at Park Town School (Lucille Davie)

Cargo Carriers, a family business, is the new owner, represented by Garth Bolton. The company is the fifth owner, having moved in at the end of 2008. The mansion will be the head offices of the company, and around 40 staff members have moved into their offices.

Bolton says he has had his eye on the mansion for 10 years but it was snapped up by Van’t Riet. It came on the market again in July 2008, and was sold to him on auction. Describing the moment of purchase, Bolton says after his bid there was “a pregnant silence, my stomach was churning, then the hammer came down, and thank God, it was mine”.

He paid R22-million and for that he gets three acres of land or five stands, in all some 14 500m².

Bolton has divided the huge house into spaces for training and offices. He plans to restore the large coach house in the grounds.

Dorm with separate rooms coverted to open-plan offices (Lucille Davie)

Conservation architect Henry Paine was called in last year to give an assessment of the condition of the house. He said that the house is in reasonable condition, with some features, like a new kitchen, or the separate rooms in the attic, having been insensitively altered. The coach house has been badly damaged and stripped of its original interior.

Paine was worried about the wooden floors – in the past they were sanded too severely, meaning that their small hidden interlocking mechanisms were worn thin and could easily break, causing each plank to collapse. However, restoration of the floors has been successful. Paine has been consulted throughout the restoration.

Paine estimates that the replacement value of the house and the value of the land together total some R70-million, making it a bargain buy for Bolton.

Fixing the house

Then Bolton did another smart thing – he appointed Ryno van der Riet as his facilities contractor, in other words, the guy who goes around noting what needs fixing, then rolling up his sleeves and fixing it.

Van der Riet says it’s been a huge learning curve for him. “I have learnt a lot. A lot of things cannot be replaced, they just don’t exist anymore.”

But what he has done is be resourceful – he has learnt to source craftsmen, either a stained-glass expert, a specialist carpenter, or a coppersmith. And he has learnt to make special tools, like the one to do jointing with bricklaying.

He has developed enormous respect for the craftsmen of old. The caste iron piping with brass bolts is so easy to access, he says. The bolt is simply knocked out, allowing easy access to the inside of the pipe, for cleaning, for instance.

He has spent the past year replacing inferior SA pine strips on the floors, with Oregon pine or deal, then carefully sanding the floors; or stripping down painted window frames and doors, bringing them back to their original wood splendour; or restoring bricked up doorways and fireplaces; or re-wiring the whole house, using the original piping; or having old windows re-weighted so that they now open, after decades of remaining shut.

He has covered some spaces that were previously sash windows that were replaced with air conditioning units, with plain wood while he waits to find replacement sash windows.

He has replaced inappropriate lighting with imitation period lighting which blends well.

The kitchen, originally with the remnants of a large chimney for a coal stove, has been modernised, as have the bathrooms, now boasting marble floors and marble counter tops.

Heating for the house was provided by a large antique coal generator which at some time was converted into a gas generator. Van der Riet has restored the gas heaters throughout the house.

The attic, which was originally a set of small rooms, each with its own fireplace, has over the years been converted into one large room, with attic windows looking out over the glorious view. It is now a large open-plan office, with restored wooden floors.

The house is perched on the edge of the ridge, with an indigenous garden stretching down the steep northern hill. The garden stretches south of the house, with a swimming pool, a gazebo and a small thatched house, as well as the coach house.

The swimming pool has been restored, and this year the terraced walkway of the northern garden will be reclaimed. Van der Riet also plans to get on to the roof with scrapers and brushes, and have it painted in winter.

What a view! (Lucille Davie)

Challenges and finds

There are still several challenges, though, he says.

Like the brass light fittings. He has learnt about something called an “ernest thread”, a small, brass ring bolt that surrounds the knob that switches on the light. He has had to source a turner to make new threads. He is still waiting to find pieces of Burmese teak, on which he will mount the brass-plated light switch.

His biggest challenge was to supply telecommunications facilities to every room in the house. He has done very little chasing of walls, running cables under the wooden floorboards instead.

“This house is built forever – it will never fall down,” he exclaims. The exterior walls are 70cm thick, and each interior wall is 52cm thick, and is reinforced with a steel beam. Over 103 years the house has developed no cracks, except for one in the cellar.

During restoration he has made some interesting finds. Under the floorboards he found an empty packet of Lexington cigarettes, priced at 6 pence, which he estimates goes backs to the late 1940s. He found old plastering tools under the floor too. He also found an old medicine bottle, with the word Poison moulded on it.

And while restoring a fireplace, he found that a piece of wood lifts to allow for the storage of rifles, in a long vertical shaft.

“I have a lot of respect for the craftsmanship in building the house. These were genuines,” he adds.

Park Town School

The Tracey family occupied the mansion until 1917, when the Park Town School took up occupation. The school had begun in Girton Road in Parktown in 1902, opened by Lord Milner for the sons of upper class families. It started as a wood and iron building, called the Tin Temple, so taking over this mansion was a huge step up.

“The school, however, was a great success, and many of the country’s eminent citizens, had their first taste of learning in it,” recounts Helme.

The founder and first headmaster of the school, AR Aspinall, moved his pupils into the school, and remained in charge for another two years. Headmaster RGL Austin took over from him, and left in 1945, to be replaced by joint owners and co-headmasters Terence Lawlor and Douglas Fraser McJannet.

The school operated successfully for 40 years, but by 1957 it was taking strain. ”In spite of every effort on their part to keep the school going, its closing is now inevitable,” reports Carole-Ann Brink in the Rand Daily Mail of May 1957. It seems the reason for closing was financial.

”The school desks, many of which bear the carved names of well-known personalities, still stand in the empty classrooms,” she continues.

Those personalities included the late Harry Oppenheimer, members of the Cullinan family, famous because Sir Thomas Cullinan found the world's largest diamond near Pretoria, Alan and Oliver Fitzpatrick, sons of the late Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, author of Jock of the Bushveld, and neurosurgeons, specialists and lawyers. Some 32 old Park Town School boys died in World War II.

The school had 62 boarders and 15 day pupils between the ages of seven and 13, says Brink. Dormitories were named after World War I battles – Anza, Ypres, Mons, Delville Wood and Somme.

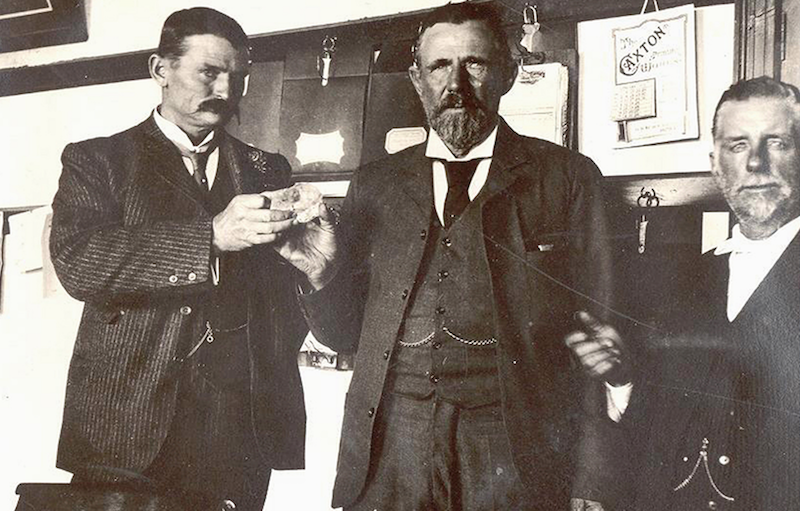

William McHardy hands the Cullinan Diamond to Thomas Cullinan (left) (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Secret passage and ghost

The attic took the name Mons, and it had a secret passage running the length of the house, providing the boys with great fun. The story goes that one night, on entering the passage, they found a box with a note inscribed: “Please leave your litter here.”

There was reputedly also a ghost in the house, referred to as “Tracey’s ghost”. Headmaster Lawlor once found two boys in an out-of-bounds part of the mansion, and reprimanded them by saying they may bump into Tracey’s ghost, recounts Brink. Their reply to this was: “Oh, but sir, we saw him. He asked us to sit down and have some tea.”

Van der Riet says that in fact there are two passages running the length of the house in the attic, as well as a central vertical passage. He says the horizontal passages can only be accessed on hands and knees. He has made good use of the passages – he is running his cabling and piping through them.

Van der Riet says he has worked late at night in the house and has never had any sense of a ghost. But one of the employees says that about two months ago she had an experience that made her hair rise and gave her goose bumps. She was working alone in the house at around 6am when she suddenly felt that someone was watching her. She never saw anyone but got up and closed her office door, and the sensation disappeared.

“I definitely think there’s something here. I felt I was not the only person in the building.”

Cullinan family

David Cullinan, a former pupil and great-grandson of Cullinan, recalls seeing the ghost. One night as a 7-year-old, he left the second-floor dormitory to go to the toilet, and at the end of the passage he saw the shadowy ghost of Tracey, which disappeared quickly. “I told everybody, but they’d also seen it. It was quite an accepted thing,” he says.

Cullinan followed a family tradition in going to the school - Tom and Roley Cullinan, the sons of Thomas Cullinan, also went to the school.

Because David Cullinan was the last family member to attend the school, he was given all the school photographs, and has several dining room tables and a chair from the school.

He recounts that the boys were allowed to bring axes to school, to go into the grounds and cut wood “to build houses”. They used to come across Afrikaans boys who they used to call “jongs”. There was some antagonism between the two groups of boys. Cullinan was shot at with a pellet gun by one of the Afrikaans boys.

Cullinan confirms that the classes were very small – up to eight boys per grade. They were given a classical British education, learning English, Latin, French, with Afrikaans thrown in, in addition to the humanities.

Some traditions continued for years. Brink says that the barber, LF Junge, cut the boys’ hair from 1906 until 1956.

Van der Riet says he is determined to fix every single thing that needs fixing in the house, knowing it will be “an endless job”. Maybe Tracey’s ghost will finally be at rest, knowing the house is in good hands.

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.