Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, James Walton tells the story of the soap houses of the Karoo and their importance to the local economy for many years. The article was first published in the 1983 edition of Restorica, the journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). Thank you to the University of Pretoria (copyright holders) for giving us permission to publish.

On some of the Karoo sheep-farms one may still find small unpretentious-looking buildings which today serve as stores or fowl-houses but which formerly played a much more important role. They are the buildings in which the farmers' wives and their servants made soap; a domestic industry which contributed considerably to the economy of the farms. Without the income from the sale of the soap it is unlikely that many of the remote farms could have been occupied until a much later date.

When Henry Lichtenstein journeyed through South Africa at the beginning of the last century he commented, as did several other travellers, on the seasonal transhumance of the stock farmers from the Bokkeveld to the Karoo. 'As soon as in the cooler season the rains begin to fall', he wrote, 'the colonist with his herds and flocks leaves the snowy mountains and, descending into the plain, there finds a plentiful and wholesome supply of food for the animals'.

'Before the inhabitants of the mountains descend into the Karoo, their fields and gardens are put into winter order. The children and slaves are sent to collect the young shoots of the Channa bushes (Salsola aphylla and Salicornia fruticosa). The ashes of these saline plants produce a strong lye, and of this, mixed with the fat of the sheep, collected during the year, the women make an excellent soap, from the sale of which a considerable profit is derived: large quantities are sent to Cape Town, where it is sold at a high price.'

William Burchell, in 1812, reported a similar soap industry in the Achter-Sneeuwberg, where 'the family, with their slaves and Hottentots, being fed with mutton at every meal, caused a daily consumption of two sheep, the fat of which was considered almost equal in value to the rest of the carcass, by being manufactured into soap. lt was, as they informed me, more profitable to kill their sheep, for this purpose only, than to sell them to the butchers at so low a price as a rix-dollar or less, and even so low as five schillings. I saw a great number of cakes of this soap, piled up to harden, ready for their next annual journey to Cape Town; whither they go, not merely for the purpose of selling it, but of purchasing clothing and such other articles as are not to be had in the country districts, but at an exorbitant price.'

The part which soap manufacture played in the sheepfarmer's life is well summarized by William Talbot: 'Sheep's tail fat was widely used in cooking and at the table; for ships' stores it was preferred to butter. In the remoter districts, however, the chronic shortage of casks and the distance from markets made tail fat as such unsaleable. Much of it was, therefore, combined with the ash of Karoo bushes, particularly the brak ganna (Salsola aphylla) to make soap or mixed with the harder goat tallow to make candles - both products economically transportable from the frontier, especially when part of the wagon load could be made up of more valuable products of the hunt such as ostrich feathers, ivory, horns and skins. Therefore the Cape sheep, whose inherent suitability to the Karoo had made the initial advance into the arid regions technically possible, continued in the second half of the eighteenth and the first decades of the nineteenth century to provide the major economic incentive to advance the frontier beyond the regions that could adequately supply the market for slaughter stock.'

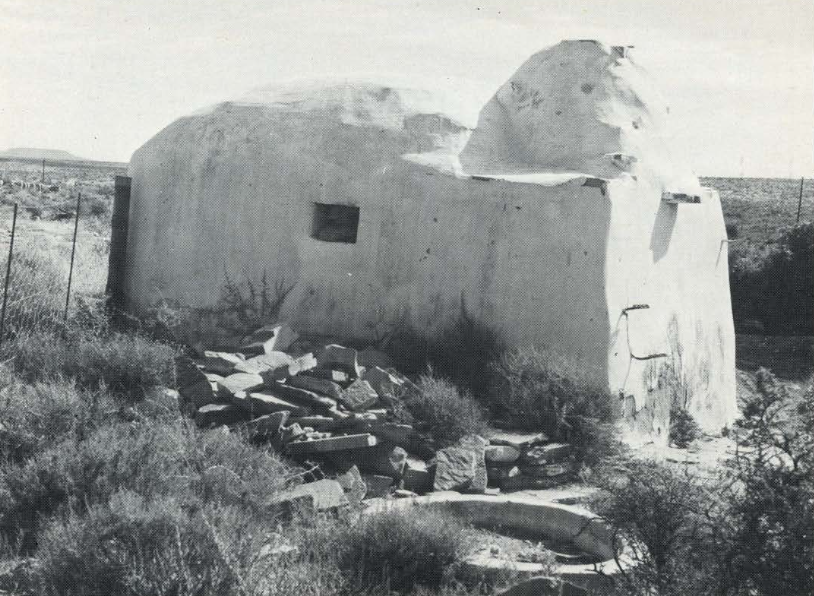

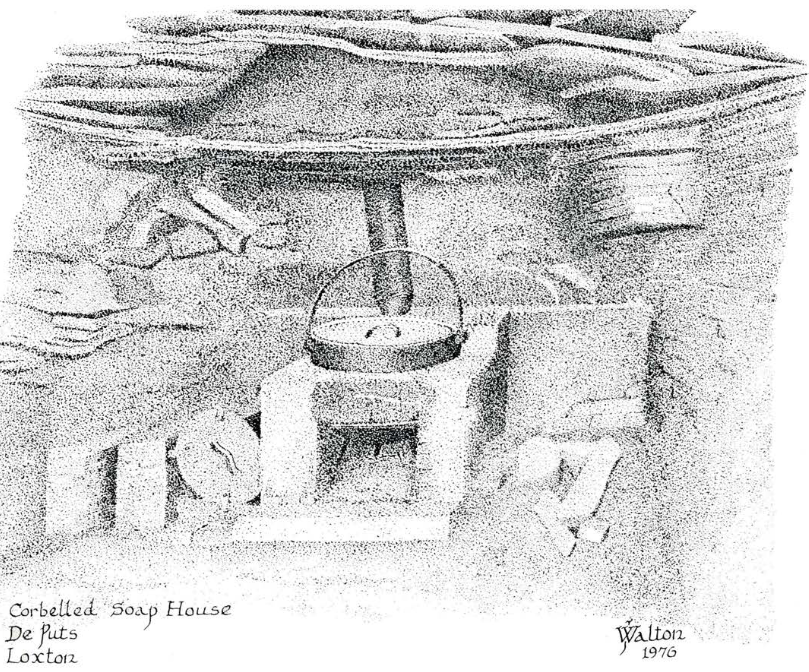

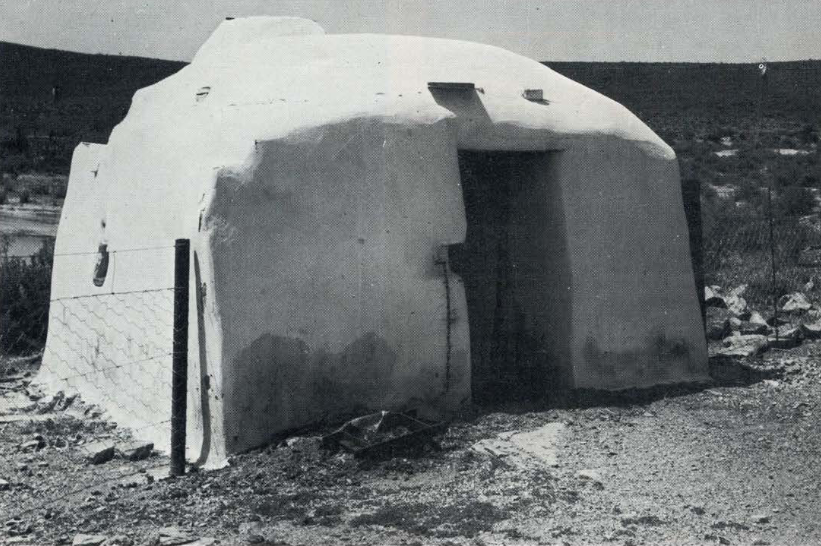

Soap making was often carried out in a separate soap house which was built in the prevailing local style. The one at De Puts, in the Loxton district is a rectangular stone building, measuring 4,1m by 3,2m externally and having walls 60 cm thick (see main image). The front part of the building, measuring 2m by 2m internally, is covered by a rather flat corbelled roof but the rear portion, which houses the large iron three-legged soap pot set in a brick fireplace, is roofed by a beehive-shaped chimney stack, thus affording a most attractive composite shape. The doorway is in the end opposite the soap pan and this, together with a small window opening in each side, provides illumination. This little soap house should be preserved, not only for its architectural interest but also as a relic of a rural domestic industry which contributed in no small measure to the early settlement of the more remote parts of South Africa.

Soap House showing corbelled domed chimney stack, De Puts Loxton (James Walton)

Interior of the soap house at De Puts, Loxton (James Walton)

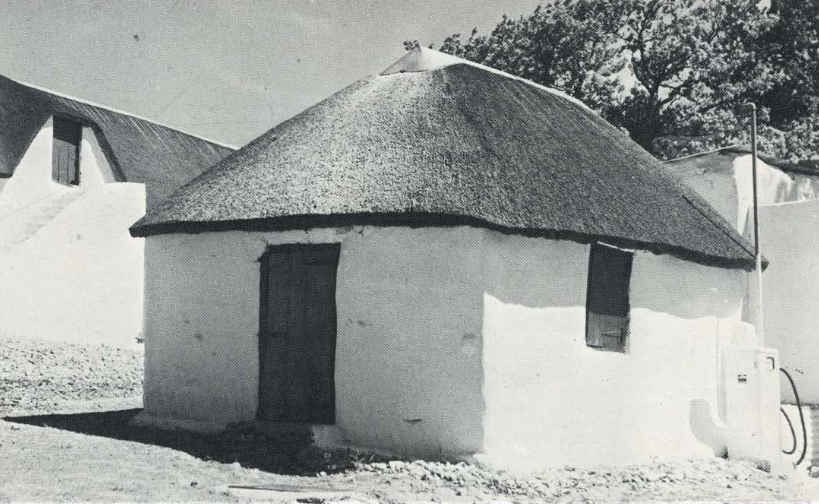

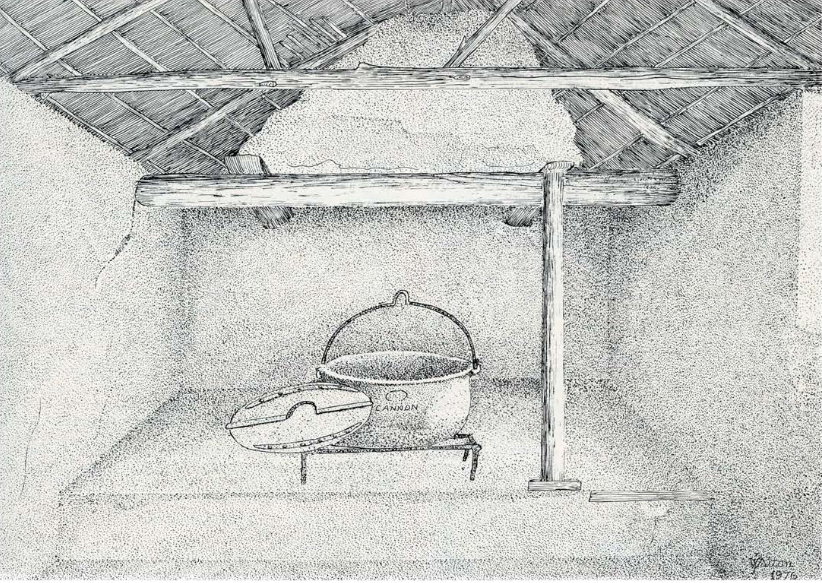

The soap house at Boplas, in the Kouw Bokkeveld, is a slightly larger rectangular building, measuring 5,1m by 4,4m, with a hipped thatched roof. The entrance is similarly placed in the middle of one end but at the opposite end, instead of a set pot, is a raised hearth, 1,25 m deep, on which is a large oval iron soap pot, standing on a locally-made four-legged iron trivet. The hood over the hearth remains but the external chimney has been removed. lt has one window opening, closed by a hinged wooden shutter.

Soap House at Boplas (James Walton 1976)

Interior of the Soap House at Boplas Koue Bokkeveld

Soap making was a lengthy process. The lye bushes were burnt and the ash was soaked in water to produce the lye, which was decanted from the ash. The fat was put in the soap pot and covered with water. This was heated and the lye was added, the mixture being stirred with a long stick. The heating continued for ten days or more, fresh lye being poured in from time to time, at the end of which time salt was added and the soap rose to the surface. This was cut into bars and stacked to harden.

The decline of this important rural industry was largely brought about by Leblanc's new process of manufacturing caustic soda from brine and by the use of palm oil instead of fat, which resulted in the development of the large Merseyside soap industry at the beginning of the nineteenth century. 'The impact of this new competition upon the rustic Cape soap industry', wrote Talbot , 'was accentuated by the shrinkage of the local market with the reduction of the South Atlantic squadron and of the Cape and St. Helena garrisons following the death of Napoleon'.

The wife of the stock farmer continued to make soap for the use of her family but, by using caustic soda instead of lye derived from the bushes, she was able to make her batch of soap in a day instead of nearly a fortnight as previously. The introduction of Merino sheep at the end of the eighteenth century heralded the change from fat-tailed sheep to wool-producing breeds and these various factors all contributed to the ultimate termination of the domestic soap industry. The soap houses which remain now serve only as stores or fowl houses.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.