Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We are very excited to publish this wonderful article from the Restorica archives (November 1976). M. A. P. Diemont Jr delves into the fascinating history of the design and construction of the old South African Reserve Bank Building in Cape Town. Today the building forms part of the Taj Hotel Complex. Thank you to the University of Pretoria (copyright holders) for giving us permission to publish. Restorica is the old journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation, today the Heritage Association of South Africa.

In September last year Cape Town’s South African Reserve Bank building - one of the city’s least known yet most fascinating landmarks - changed hands. It was bought by the Board of Executors, the oldest trust company in South Africa, and although the deed of sale was signed in 1968, transfer was delayed until 1975 when the Reserve Bank’s new foreshore premises were ready.

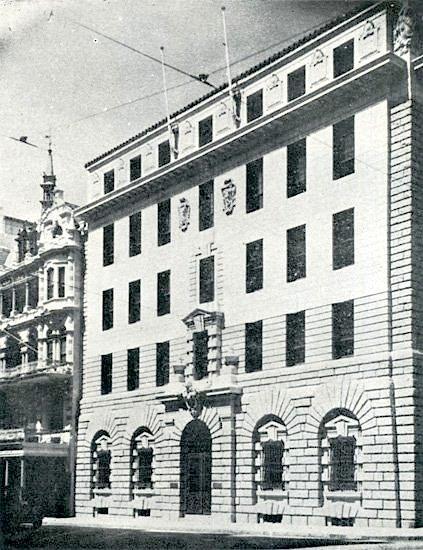

Situated in the old, conservative heart of Cape Town - between Adderley, Wale and St George’s Streets - this magnificent old building styled on the lines of Florence’s Pitti Palace, has the distinction of occupying the highest municipally rated land in the country.

The South African Reserve Bank Building (Architecture in South Africa - L Cumming-George)

But it is the building itself and its quaint history, probably never before publicised, that deserve attention. It forms yet another fascinating facet of the mother city, and it is thanks to the beautifully handwritten notes compiled by one of its architects that we know as much about it as we do. In fact the writer, Mr Reg de Smidt ARIBA, who passed his notes on to the Board of Executors, concluded by expressing the hope “that this description will be of interest, since I am under the impression that I am the only man alive who could supply it”.

The building is not particularly old; in fact its design was only conceived in the latter half of 1928 when an architectural competition “open to all registered architects in the Union of South Africa” was held for a building in Cape Town to house the Reserve Bank of South Africa. The competition was won by the eminent architect, James Morris, FRIBA, a Scot who had been practising architecture in Cape Town for many years. Others involved in the construction were Mr Reg de Smidt (chief architectural assistant), sculptor Ivan Mitford Barberton, and contractors, Adams and Nason. Mr Martin Adams, incidentally, was later to become a mayor of Cape Town

The Florentine Palaces, upon which the Reserve Bank building was modelled are built of stone, the bottom facade heavily rusticated and rugged in appearance. The bottom storey was usually fortified, and formed the granary and food store of the building, the upper floors being residential. In basing a bank design upon that of the Pitti Palace, the intention was to symbolise the financial strength and stability of the Reserve Bank of South Africa. Thus Paarl granite was chosen as the material for the St George’s Street and Wale Street facades. and the lower storeys are heavily rusticated as is the prototype building in Florence.

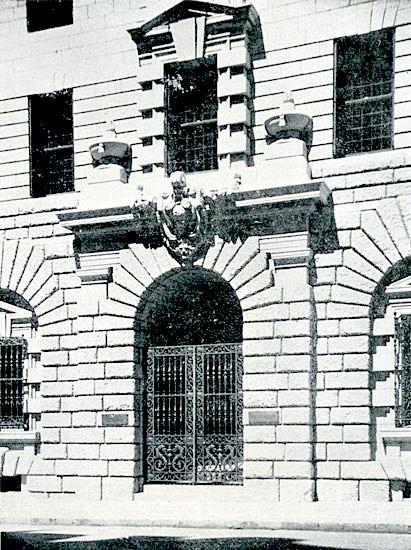

Entrance to the South African Reserve Bank Building (Architecture in South Africa - L Cumming-George)

Capetonians might be puzzled when they see the Paarl granite facade of the Reserve Bank illuminated by a pencil-slim spotlight radiating from the bronze lamp at the corner of Wale and St George’s Streets. It casts its “symbol of steadfastness” because the Board of Executors have decided to carry out one of the wishes of James Morris.

Another of the architect’s wishes which has been honoured for the first time last year was the flying of flags. Until recently the two stainless steel flagstaffs, housed in sockets on the St George’s Street facade above the cornice, have served as nothing other than catchment posts for rainwater or targets for pigeons. In 1929 they were meant to fly the two flags of Union “between the hours of sunrise and sunset”, but this was never done and we are of course no longer a Union. However, the Board have decided to put those flagstaffs at last to their proper use, and during hours of daylight they carry the South African flag.

Initially, odds against the building drowning were few as sub-soil water seeped - and still seeps - steadily into a sump from which it is drained day and night by an electric pump operated by an automatic float switch.

In the basement, hewn from solid rock, the floor is double constructed of waterproofed, reinforced concrete. The two strongrooms have reinforced concrete walls almost a metre thick, the cement made to specification by the Cape Portland Cement Company and protected by two doors which cost £500 each at the time of construction.

Surrounding the strongrooms is a 3,25m wide corridor the patrolling area for two watchmen whose task it was to punch a bell push every half an hour, alerting the central police station that all was well. If the bell was not sounded on time two policemen were supposed to rush down to the bank (presumably they had duplicate keys) to investigate.

For every month of 1929, James Morris bludgeoned the Astronomer Royal (Cape) into measuring the position of the shadows on the skylight. The angle of the sun would create variations of light intensity in the central banking area, and Morris wanted direct sunlight in the Banking Hall.

Above the skylight, there is a central open light well which provides light for the upper storey corridors, the walls of which are supported on a concrete beam and cornice, which in turn are supported by four single monolithic marble, fluted Doric columns.

Originally the marble for the columns was to be quarried in Sweden and modelled in Belgium. The quote for the Swedish green marble was £325 a column and for the Swedish Cippolino, £345 a column, Morris chose the more expensive Cippolino - a mottled green and cream.

While construction continued, the walls of the light well were supported by massive old yellowwood beams - a fire hazard. When the columns arrived, the wily Scot, Morris, was convinced the cheaper marble had been substituted at the higher price.

A court case proved him right but also aroused the ire of the taxpayers and, inevitably, a journal of the time, the South African Review, asked: “What does the government mean by spending nearly £ 1 500 of the taxpayer’s money on four columns?” The columns were scrapped and cheaper though nonetheless attractive cream and brown Portuguese Skyros marble was quarried in Portugal.

James Morris’s sculptor, Ivan Mitford Barberton, was also rapped by Morris - over his knowledge of feline anatomy. Bronze medallions of a lion ‘passant’, the badge of the Reserve Bank, displayed at each corner of the of the elaborate bronze grilles on the front facade had to be made. Barberton took his clay models of the lions to Morris for approval, but was criticised for omitting the poor creatures private parts. Barberton assured him - as he had experience of hunting lions in Kenya - that members of the cat family always concealed their genitals behind the back leg.

Old Reserve Bank Building Cape Town (The Heritage Portal)

The three way hip tiles at the corner of Adderley, St George’s and Wale Streets would not have been a feature of the building had not Morris had a taste for perfection - and the expensive. He had them modelled, cast and burnt at great cost and took care to order spares in case of aircraft crashes or breakages by workmen cleaning gutters. Today the spares are still stored in the loft corner of the building - hopefully beyond the reach of crashing aircraft.

Morris was not going to have a vulgar external lift spoiling the lines of his classical Pitti Palace tile roof so he put the lift room in the basement, doubling the normal length of the lift cables.

Despite Morris’s whims, or perhaps because of them, the Reserve Bank building is still considered to be his finest contribution to architecture and is greatly appreciated by those of his contemporaries still alive.

What of its future? The Board of Executors, a company owned by approximately 450 shareholders and established by an Act of Parliament in 1839, decided to make the purchase because the building adjoins their own historic premises. They saw in it a valuable investment and quarters to cater for future expansion.

Tenants for the immediate future have not yet been established. Who knows? Perhaps it will be the Trust Bank, with the thin pencil of light symbolising modernity.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.