Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Few engineers in the 19th century went to university and most were articled to an established practitioner, by which means they would eventually be admitted to Associate Membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers. But in the early years the profession was not established, pupillages were scarce and the Institution did not exist. Many gained experience as labourers and artisans and were recognised as engineers when they emerged from the pack to plan and execute their own projects.

One achiever who took the hard route was James Cameron, who joins our list because he became the second City Engineer of Cape Town.

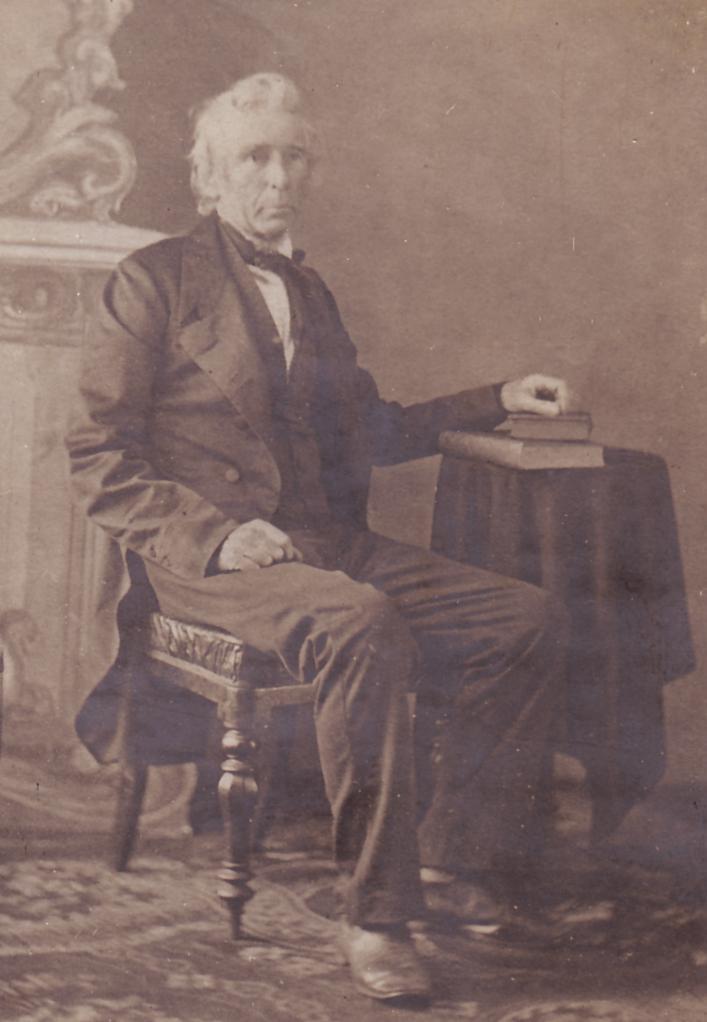

James Cameron

He was born in the village of Murthly near Dunkeld, Scotland in 1800. After attending the village school he studied mathematics and chemistry at University in Perth, and he was then apprenticed to a carpenter. At the age of seventeen he became fascinated by the work of missions and missionaries, and especially about the need in Africa for "persons acquainted mechanical arts and industry" and he decided to improve his skills with a view to serving abroad. In 1824 he offered his services to the London Missionary Society. This organisation was only too keen to enlist artisan-missionaries who could bring enlightenment to darkest Africa not only by preaching, but by teaching practical skills.

James moved to Manchester to gain some experience with cotton machinery, which was regarded as useful equipment for an emerging country. His path to Africa was however temporarily blocked.

Very sensibly the LMS insisted that their missionaries went out into the field married – and James had difficulty in finding a young lady who was willing to share the unknown with him. Eventually he met Miss Mary Ann McClew a brave lass with the required missionary spirit – but her parents objected and the Society felt she was unsuitable. There were some awkward moments before the obstacles were overcome, and in May 1826 James and his bride sailed for Madagascar. After a voyage of seventy-seven days they reached the capital Antananarivo.

Madagascar in those days was a formidable challenge. Several missionary colleagues perished within days of reaching the island, victims of the dreaded Malagasy fever. Those who survived had to contend with unpredictable natives whose customs, if not understood, could end in torture or death by poison.

Fortunately the Camerons arrived in the reign of King Radamo, an enlightened monarch who appreciated way in which the missionaries could aid the development of his people through economic as well as spiritual education. James taught chemistry and carpentry to the locals and instructed them how to make bricks and spin cotton. When a printing press – an essential adjunct to spreading the Gospel – arrived without the printer, who had succumbed during the voyage to Africa, he assembled the machinery and taught himself to operate it. (Copies of the first chapter of Genesis printed in this way are preserved in the South African Library.)

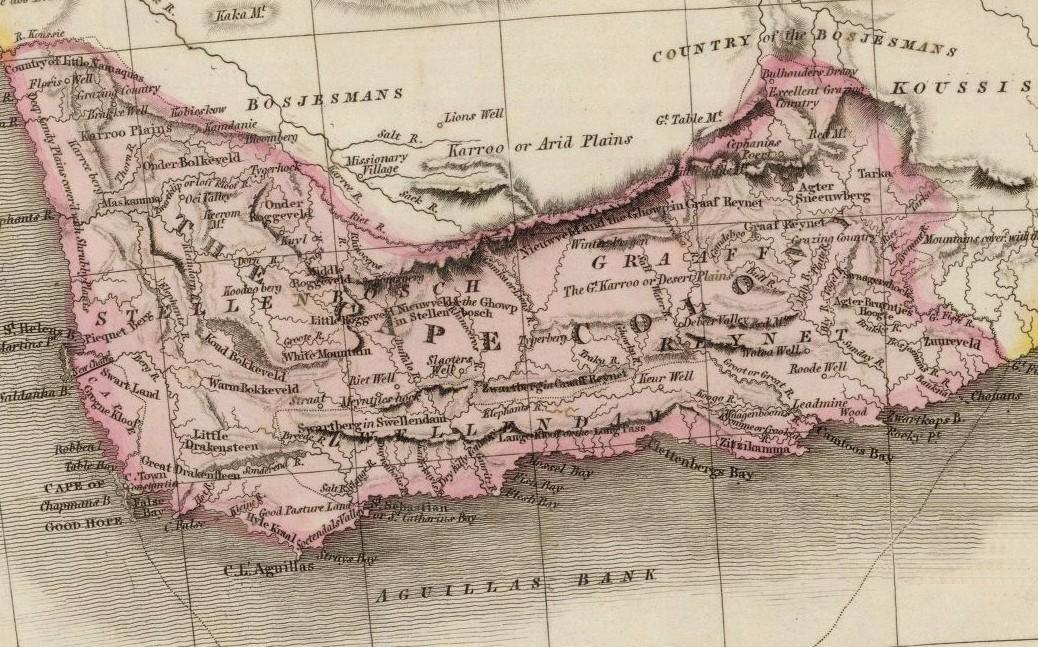

Then the town needed a mill, and the mill needed water, and somehow the resourceful Cameron acquired the engineering know-how to build a canal and a reservoir to supply the needs. He also surveyed and produced a very professional map of the town. There are no records of how he gained the required skills or where he obtained the instruments and materials in such a remote place.

In 1828 Madagascar fell under the rule of the despotic Queen Ranavalona who banished Christianity and expelled the missionaries. Cameron soldiered on until 1836, when he and his family relocated in Cape Town, where he soon became established as a contractor and surveyor.

View of Cape Town, Table Bay (Thomas Whitcombe)

In 1856 the Municipality of Cape Town was but two years old and the town was suffering from years of neglect. The streets were dusty in summer and quagmires in winter, the old canals had become open sewers, sanitation was rudimentary and inefficient, and unsanitary practices such as pig-keeping in small backyards were rife.

The first Town Engineer, Woodford Pilkington (son of George Pilkington), returned to the Colonial Service after just a year in office, and Cameron was appointed in his place.

One might wonder how an untaught artisan, with skills developed in the most primitive conditions, could fill such a challenging position. No matter; Cameron was equal to the task, macadamising streets, paving the Buitengracht canal, providing a water conduit between Camps Bay and Sea Point, and reporting even-handedly on several other contentious matters.

But the new City Fathers were loath to undertake any major works and were against increasing rates, and so little could be done about the lack of proper drainage and sanitation. The Colonial Government then stepped in and instituted a "Select Committee of Enquiry into the Sanitary State of Cape Town" under the chairmanship of the redoubtable John Fairbairn. Cameron was summoned to present evidence. Again, it might have been suspected that his background would have been inadequate to face such a formidable inquisition, and again he displayed his unflustered competence.

He was questioned at length about his knowledge of technical and financial arrangements in Scottish cities. He was acquainted with Perth and Edinburgh "in both of which towns they had an abundance of dirt and an abundance of debt". However he had well-motivated proposals, accompanied by comprehensive estimates, for installing sewerage in Cape Town.

Cameron calculated that the cost of trenching would be twopence a foot, and the average cost of material (imported from Europe) was a shilling a foot. The total cost would be £20,000, which worked out at £5 per household. As the existing charge for nightsoil removal was £1 per year, it was presumed that a householder would recover his outlay within five years.

While the proposals were well-received, the fledgling City had no capacity to raise loans, nor sufficient water to operate waterborne sewerage, and so the plans were put on hold.

Cameron was not in office to take his scheme any further. Later in the year 1857, the "extremely argumentative" artist Thomas Bowler was returning home one dark night when he drove his horse and cart over a mound that had been raised on the corner of St Georges and Longmarket Streets. The cart tipped over and he claimed damages of £3 from the municipality. The Council decreed that the Engineer, Cameron, should pay the claim out of his own pocket. The feisty Scot told the Councillors what they could do with their roads, sewerage and the job, and resigned on the spot. (Bowler never got his money.)

In his spare time Cameron became one of the first skilled photographers in the colony, and an early daguerreotype of his fellow Scot missionary-explorer David Livingstone is one of the authentic portraits of the famous Victorian. One of the earliest known local outdoor photos was of his future daughter-in-law Miss Ellen Solomon of the well-known Sea Point family.

In 1863 the political climate in Madagascar improved, and Cameron returned to his beloved Antananarivo where he resumed his good works, building several churches before he passed away in 1875.

His son, also James (1836-1901), was a noted South African educationalist and became the first registrar of the University of the Cape of Good Hope. A great-great-grandson, Ralph Cameron-Williger, has been a well-known consulting engineer in a Cape Town practice.

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.