Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

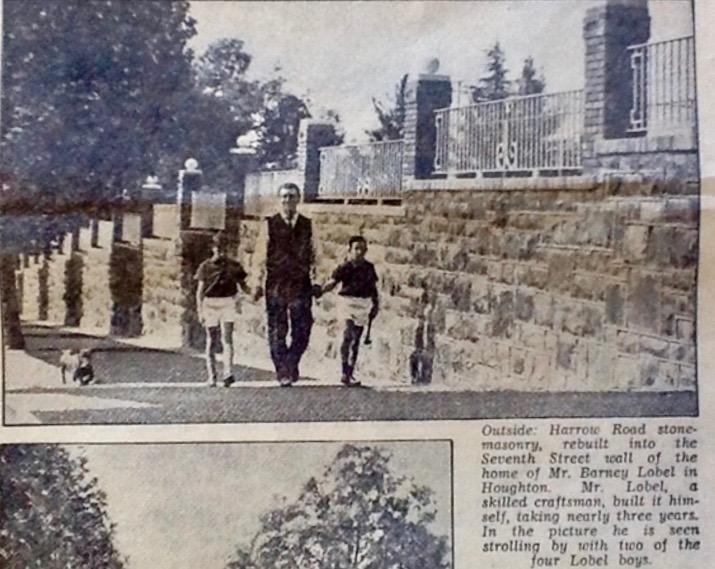

Over the holidays I was given a unique Christmas gift by my friend, Peter Digby who shares my enthusiasm for Johannesburg heritage items. It was a single old yellowed newspaper page, dated 9th November 1965, from The Star Newspaper. The page was saved in a cupboard of the Digby home because it carried an unusual story. The headline was: “Fine old stone in a new wall“. The article tells the story of a Mr Barney or Bernard Lobel (his name was actually Barnett Lobel) who rescued and saved the precision cut, dressed and shaped grey quartz and granite stone that was retrieved from the precinct and park when the Harrow Road (now Joe Slovo drive ) was widened and reconstructed in the late 1950s.

Johannesburg walls and rocks

This yellowed fragile newspaper cutting set me thinking about Johannesburg walls and streets. If you look around the city, you will find examples of early stone and rock taken from the hilly ridges or from mining operations. Stones were quarried and it was all there for the taking. Since gold was embedded in a series of gold bearing reef and seams that ran for miles to the south of the city and descended at a 45% angle, extensive underground blasting was required and a great deal of quartz was excavated which could be used for building. Mine rocks were recycled into all sorts of structures from pioneering days. These rocks were all essential building material ahead of the making of bricks.

These days visitors often comment on our high walls but they have been a feature of many old Johannesburg suburbs such as Observatory, Parktown, Westcliff and Houghton. Instead of regarding walls as security barriers, one can seek out a variety of beautiful old walls.

For example, from quite an early date the NZASM engineers made use of rock and natural stone as building material for their station buildings (see Artefacts for details). De Jong (1988) comments: “For the construction of its buildings and other structures the NZASM engineers preferred natural stone like sandstone, ironstone (dolerite) or hornstone ('blouklip'). These building materials were readily available at many places and obtainable free of charge.”

Skills of expert stone masons were in demand. I recently visited a heritage colleague at his house in Escombe Avenue Parktown. His home dates from 1906 and the wall was built of “blouklip”, which was sourced from Crown Mines and discarded during mining operation. This hard quartz was handled by skilled stone masons and was called “hammer dressed”. This meant that each stone had to be chiselled to create squared corners which was no mean feat since the stone is extremely hard. To build a wall with such stones required assessment and selection of each individual stone.

The minimum of mortar needed to show. In Britain there was a rural farm tradition of building walls and setting boundaries with a dry stone walling technique and one occasionally sees such work surviving in Johannesburg. Crown Mines blouklip was also used to lay gutters and kerb edges to pavements. You can see such engineering feats on the streets of Parktown West for example.

Harrow Road

Let’s start by placing Harrow Road in an earlier context. It is today named Joe Slovo Drive and we remember a struggle hero and communist party leader with a new name. But Doornfontein and north eastern Johannesburg were part of the expansion of the early thrust northwards of Johannesburg, taking the mining town beyond Bezuidenhout Valley and towards Orange Grove via Louis Botha Avenue. Yeoville had made its appearance on the maps of Johannesburg of the 1890s (see the Plan of Johannesburg 1896). Roads, albeit rough and ready were key to suburban and township developments. The significance lay in the elevation of the ridge and the positioning of the city’s earliest water reservoirs. Thus Harrow Road connected Doornfontein to Yeoville and was the route of migration as the new suburbs to the north east opened up (Berea, Bellevue, Highlands and then Observatory and down towards Fairwood by 1906).

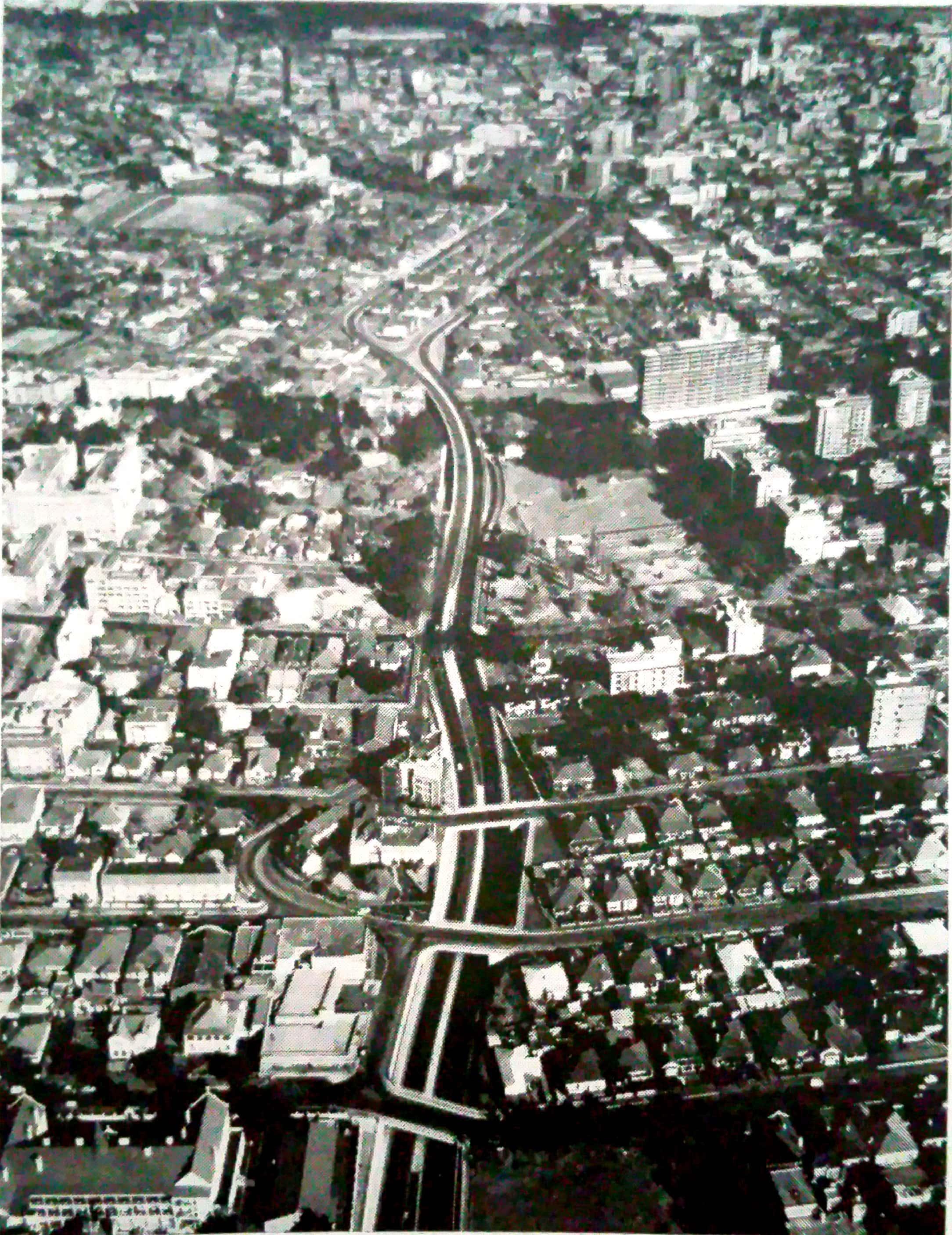

By the 1940s and 50s, Johannesburg needed to rethink its road system, and began to put together plans for improved roads and better access to the city. By the sixties the engineers developed the M1 and a ring road motorway system in line with thinking about city planning in other parts of the world. What was required were encircling ring roads and intersecting principal access roads leading to the Central Business District. The Harrow Road improvement and conversion to a thoroughfare or freeway was the first of Johannesburg’s freeways and cut a swathe through Yeoville, Berea, Bertrams and down into Doornfontein. The new development changed the geography of the north east, provided speedier access and required a change in the line-up of the road.

Photo of Harrow Road from above (Johannesburg Saga)

John Shorten in his mammoth 80th anniversary official commemorative volume, Johannesburg Saga published in 1970 (some 4 years after the 80th birthday), tells the history of the major road programmes of the city and efforts made over the years to improve access to the CBD (see chapter on the History of the City Engineers Department pages 568-581). The major Johannesburg questions were what to do about transport and traffic, should Johannesburg’s transport be private or public, was Johannesburg the city of the train, the tram, the trolley bus, the private car or the shared taxi? Johannesburg’s answer to these questions during the apartheid era was to embark on both improved railway networks as well as a traffic plan and road network; airline links were way behind. In 1954 it was decided to back a traffic scheme together with a road improvement network, providing for an urban freeway system projecting forward over a ten year period. Shorten places Johannesburg roads into a context and comments: “the first major portion of the traffic plan to be undertaken was the Harrow Road reconstruction scheme with its underpass at Louis Botha Avenue, its overhead Road bridges at Alexandra and Barnato Streets and Joel Road (in Yeoville and Berea) and its fly-over at Saratoga Avenue”.

It was this development that gave Mr Lobel his opportunity. I was a child in the fifties and remember visiting a great aunt who lived in a house on one of the streets of Berea. Her house was demolished to make way for one of these overhead road bridges.

Harrow Road under construction (thanks to Marc Latilla for posting this photograph on his website Johannesburg1912). It is evident from this photograph that the original route of Harrow road was much changed.

Shorten also explains that if we go back to the Johannesburg of the 1890s, when Charles Aburrow was the Town Engineer, Ferreira’s mine supplied 150 loads of mine stone which "bound by oudeklip” was to be the standard form of Johannesburg street for many years. The old saying that Johannesburg streets were paved with gold, actually had a literal meaning as much of these old mine rocks contained traces of gold bearing ore!

Mr Lobel's opportunity

All this does not quite answer the question as to where Lobel’s stones for his Houghton wall happen first to have been used on Harrow Road. David Lobel recalls that the stone that was relocated to Houghton came from the walls surrounding one of the parks and the wall was then demolished. My guess is that this could have been a second relocation of hard grey or “blou“ (blue stone) that originated in the mines.

The Lobel family recall that driving through the road engineering site that Harrow Road had become, Mr Lobel, a man of energy and vision spotted an opportunity. He saw load after load of dressed and hammered stone that had once bordered the park on Harrow Road being carted away. “All that wonderful stone... it’s just what I could use for the walls of my house”. He arranged with the demolishers to be given the stone and carried it to his family home at the corner of 7th Street and 8th Avenue in Lower Houghton. He then set about building the wall surrounding his corner property which reaches close to 100 metres along 7th street. It was a labour of love and a passion. It also saved a little of Johannesburg’s history.

Lobel was a skilled stone mason and bricklayer but he also made use of old time, Johannesburg craftsmen who by the sixties were a dying generation. Stone by stone his wall grew; it was a work of art and a massive enterprise over a three year period, as it enclosed his 2.5 acre stand. The Star reporter also informs us that Mr Lobel sold off surplus stone to pay for the mortar he used. David Lobel recalls that his father used many stones within the house as well. Lobel built with an eye on a hundred year lifespan.

Few people today driving past this Houghton wall realize its earlier history or its significance.

The wall built by Barney Lobel in the sixties. This photo from The Star of 9 November 1965 shows the Lobel wall at its finest, this was the frontage of the completed wall on 7th Street, corner of 8th Avenue.

Who was Barney Lobel?

According to the newspaper article he was a former billiard saloon keeper and a race horse owner. He won R160 000 on Colorado King in the 1963 Durban July (Colorado King, one of those legendary and famed winners, was the winner that year). This must have been on betting; he did not own that famous horse.

Barney Lobel was a family man, a father of four sons (David, Richard, Brent and Robert) and husband of Esther. I set about trying to find Mr Lobel. His dates were 1908 to 1973. His sons were educated at Wits and through the Alumni network I made contact with David Lobel and learned all about the family’s history. Today, David lives in New York and we had a long conversation. Barnett passed away but Mrs Esther Lobel is alive and well aged 95.

Barney’s name was actually Barnett but he was called Barney and Bernard by his mother. He was born in Adelaide, Australia where an earlier generation of Lobels had settled having emigrated from Wales. There were two brothers of Barnett's father’s generation and one emigrated to Rhodesia and one to Australia. Strangely, the Australian family did not fare as well as the Rhodesian family and when Barney’s father died young, his mother was left with a young family of seven. Barney was the eldest and having heard of his successful uncle in Rhodesia who had established a prominent bakery business in Bulawayo (still in existence as Lobels biscuits and bread though no longer owned by the family), decided to make the journey across the Indian ocean. He hoped for a better life in Rhodesia when the young empire country welcomed new talent. Barney was 17. He was a man with relatively little education, but became a craftsman, a sheetmetal worker, a plumber and a stone mason. All of these skills could be applied to good effect in the building trade; his talents were in demand as young countries and new towns were built in Southern Africa. Barney was also a keen sportsman (he was a talented boxer) in Rhodesia of the twenties and was selected to represent Rhodesia at the Olympic games but could not afford to participate.

In the later 1920s Barney took the decision to settle in Johannesburg and entered the building trade. As he succeeded in this sphere, he gradually paid for his large family to join him from Australia. The family settled in Observatory and Johannesburg became his passion. He prospered in the building and construction world and owned horses and placed bets. He married his wife Esther relatively late in life and had four sons. Over time Barney entered the real estate business; he was entrepreneurial and enterprising. The kind of second generation building pioneer of Johannesburg as it blossomed in the post war expansion of the thirties.

His home in Houghton represented the pinnacle of the success of this self made man. He built his house and paid attention to fine craftsmanship; he planned a family home that would last and indeed his home was a showpiece of design. He collected antiques; being a craftsman he had an eye for quality. David recalls his father’s comment, “they don’t make things the way they used to”. He added “an antique reveals the soul of the person who made this”.

Building the Lobel Wall

The wall Barney retrieved from Harrow Road was his homage to past craftsmanship and his adopted city; he could not stand by and see fine dressed, cut stones lost forever. As Johannesburg grew and the demand for labour and spiralling buildings meant processes had to be simplified, stone masonry became a dying craft. Barney wanted to save the stones of Harrow Road, recut and reshape them where necessary to build his three foot thick, perimeter wall to his Houghton property. He stepped in to do a business deal - realizing that the Harrow Road stonework dated back to the 1890s and ought to be preserved; he supervised the dismantling of the park wall and arranged for the transport of the stones to his property. David recalls there were stones everywhere and over a period of two years Barney and an architect (unknown name) built his wall. As mentioned earlier, it was a labour of love and he employed several old time stone workers to help him. The cut stones found new locations in the garden, lining the swimming pool, along the wall, and inside the Lobel home.

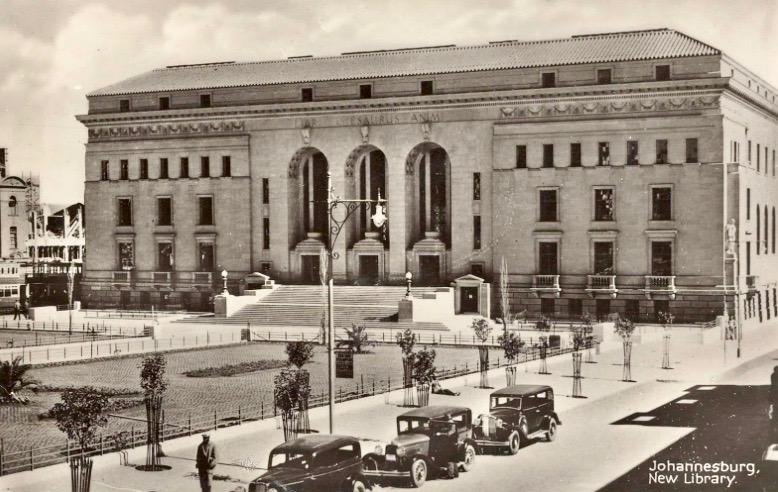

The Lobel house too was a masterpiece. Lobel was a perfectionist who not only built his wall but also his home, a swimming pool (reinforced with railway lines for strength), a tennis court, rolling lawns and a two car garage that doubled as a ballroom cum play area. Each new feature and addition was supervised. When the parking garage was built under the Library Gardens (the Harry Hofmeyr garage and today owned by the Gauteng Provincial Legislature), Barney saved and took home the lights and lanterns of the old Library Gardens.

Johannesburg’s new library as it was in the 1930s – John Perry of Cape Town was the Architect. Some 25 years later Barney Lobel saved the street furniture

Barney had an eye for history. Sealed within the gateposts at the main entrance to his property was a metal cylinder containing a time capsule of newspapers of the day, some banknotes, coins, a letter telling how he came to build the his wall and some photographs of his wife and sons. All memorabilia of the sixties.

Mrs Esther Lobel, photographed against one of the main gateposts of her home (The Star)

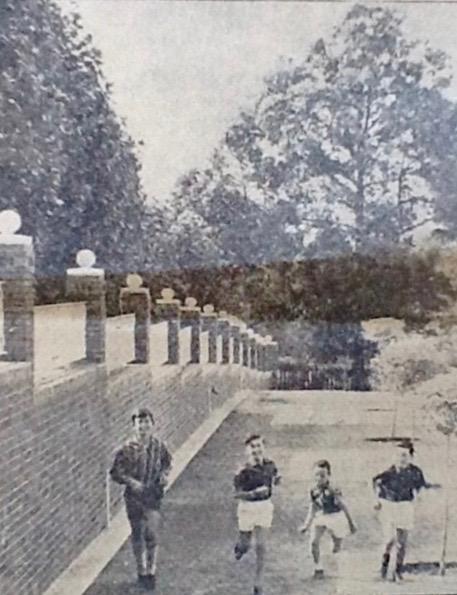

Photograph from The Star (9th November 1965) of the four Lobel sons running alongside the inside of the Lobel wall – the photo shows the wall to have been lined with facebricks on the inside within the garden of the property.

There is a further poignancy to the Lobel story. Barney’s closest friend was a Chinese man (David recalls him as Uncle Lao) who Barney had met on his sea travels to South Africa. The ship stopped at Mauritius and it was a place that appealed and remained in his memory. In the sixties, Barney decided to go on a holiday to Mauritius and spotted an opportunity. Being the entrepreneurial, enterprising man he was he was introduced to the mayor of Mauritius and successfully negotiated to acquire the mining rights to Mauritius as he felt that the mining potential of this idyllic island country was waiting to be exploited. Mauritius with its volcanic origins does indeed have an unusual geology. Lobel tried to find financial backing for his Mauritian mining scheme back in South Africa. Mauritius of the sixties was a very different place to the hotel and luxury resort world created by Sol Kerzner. However, one day a wealthy mining man arrived at the Lobel home in Houghton and came up with an offer to buy the house. Barney Lobel was persuaded to sell his unique home because the mining man promised that he would back the development of the Mauritius mining potential. Sadly once the deal was done and the Lobel family left their family home, the Mauritian side of the deal fell through and nothing further came of the mining development.

Barney Lobel died at the age of 67 in 1973 and is buried in Westpark Cemetery.

The Wall today

Acquiring this newspaper cutting, set me off on a chase. Was the wall around Lobel’s Houghton Home still in place? Peter Digby and headed out to the corner of 7th Street and 8th Avenue. We were in for a disappointment. The magnificent wall of Mr Lobel had been altered, lowered and remade, but some stones remained perhaps to a height of about three feet. The home is called Arcadia, not to be confused with the Phillips home by the same name on Oxford Road (now part of the Hollard Campus). From street level you can’t see much within the gardens and property. Large grandiose metal gates with a guard house enclose the property. There is a tall wall, you can’t see over it. The wonderful Harrow Road stone work has been diminished in scale and significance. Alas the philistines have been at work. It was a sad visit down a Lower Houghton Road. There are grand old plane trees on the pavement. From what we could see from outside the property the house had been modernized and altered. This is Johannesburg of the 21st century.

What remains of Barney Lobel’s wall in December 2017 (Kathy Munro)

It had the virtue of still being a private home and I spotted a tennis court and an ostentatious fountain down the driveway. We were peeping toms. So many of the surrounding large properties and homes of Houghton have been demolished and flattened and the remaking and rezoning of the suburb has meant that many of these one and two acre stands have become ideal tracts of land for redevelopment with new developers determined to make their fortune with the building of smart townhouses and cluster homes. One only has to drive down Houghton Drive or Central Avenue to see what has changed and how little of the Houghton of the thirties remains. Houghton is on its way to “densification”, and the large gardens are being built over.

Detail of Barney Lobel’s wall – what remains today - its there but not recognized. Notice how skilfully and beautifully the stones have been chosen to be positioned, large stones mixed with much smaller ones.

The Lobel Family today

It would seem that the Lobel family formed part of the Jewish emigration of the seventies and eighties. All the sons, graduates of Wits University, have done well. The family had brains, versatility, talent and inherited their father’s joie de vivre. David Lobel was a B Sc graduate of Wits (1975) and then went on to achieve an MBA at Stanford University. He founded Sentinel Capital Partners, a private equity company. The second son, Richard made a career in computers and voice recognition systems. The third son, Brent returned to his family’s Australian roots and lives in Sydney. The youngest son Robert chose to make his career in real estate development.

The main entrance of Arcadia in Houghton. Could the Lobel time capsule still be there? Has it been excavated and discarded during various modernisations? (Kathy Munro)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.