Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

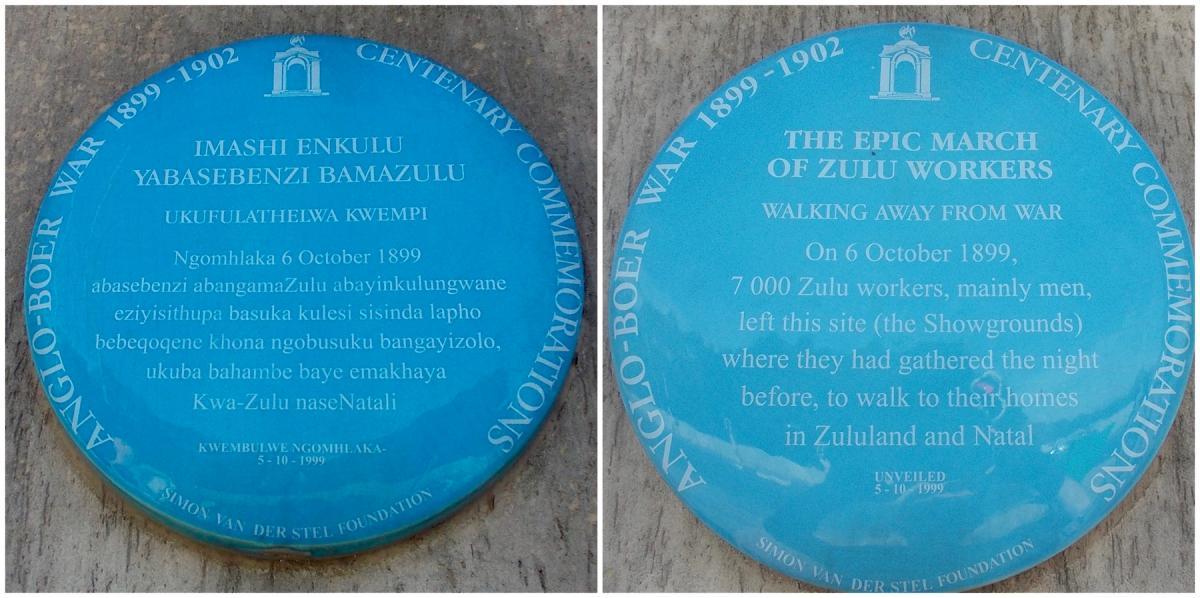

Just prior to the outbreak of the Boer War, the small mining and railway village of Hattingspruit, only a few kilometres north of Dundee, grabbed some reflected limelight. This was due to the incredible physical exertion of 7 000 Zulu workers who walked from the Witwatersrand Goldfields back to their homes in Zululand.

The logistics of this march were organised by John Sydney Marwick. At 24 years old he was a fluent Zulu linguist, and the Johannesburg Agent for the Natal Native Agency, responsible for the recruitment and personal affairs of several thousand Zulu workers employed on the mines. His Zulu nickname was “Muhle”.

John Sydney Marwick

The discovery of diamonds and gold and the subsequent mining operations had revolutionised the country. There were far reaching changes in the social, political and economic life of the country and its inhabitants. A cheap and constant supply of labour was needed and by 1899 100 000 Africans were employed on the gold mines.

Once it was clear that war was going to break out and that the closure of the gold mines was imminent, the question arose as to what would happen to the mine workers Many of the mines shut down and 78 000 workers sought refuge outside the Transvaal.

According to Thomas Pakenham’s The Boer War:

In terms of human misery, the chief sufferers from the decline and fall of the Rand were not the Uitlanders, but the African mineworkers from Natal … they were the “mine-boys” and the artisans. Now their employment had gone. They had little money saved and the Boers were quite prepared to let them starve on the veldt.

The only way to resolve the problem was to bring these people and their “hangers-on” home before war broke out. The Boers refused to provide rail transport, so the whole multitude was forced to walk back to Natal, a distance of over 400 kilometres. Apart from the navigational and provisioning problems, the Boers were on edge at the presence of a large body of natives marching through the country.

John Marwick negotiated at length with the Transvaal government and the Department of Native Affairs, to get the displaced Zulu workers back home. With all trains requisitioned for military use he realised the only way to get the men home was to walk them back. He eventually received permission so long as they all stayed together. “Child of the Englishman” the Zulus called to Marwick, “gather the orphans of the Zulu”. Hlobeni Buthelezi offered to be head marshall and to collect suitable men to assist him.

Rations were purchased, 70 ill men were put on trains that were still running and final preparations were made for the long march back to Natal and their homes.

Marwick sent a telegram to his employers “So that my proposed action may not embarrass you, please suspend me from office. If I get (the) natives through without loss of life, you may do as you please about reinstating me.”

Reluctantly he was given permission and on the 6 October lead 4000 men out of Johannesburg and then returned for the rest.

For 10 days and 400km, Marwick was as good as his word, making the perilous and difficult journey walking alongside them, assisting, cajoling, carrying infants, putting exhausted men on his pony, negotiating with local farmers for food and soothing the ruffled feathers of Boer bureaucrats encountered along the way. He was accompanied by Guy Wheelwright, Manager of the Germiston Branch of the Natal Native Agency, and W.A. Connorton from the New Herriott Mine.

The route took them to Heidleberg, Standerton, Charlestown and to Newcastle, where some dispersed via Ngogo and Dannhauser to their homes. On 15 October they reached Hattingspruit and for the price of £1 they could buy a train ticket to the station nearest to their homes. As many did not have the money, they kept walking.

Close to the Natal border Marwick had to negotiate with Gen Piet Joubert for passage through the Boer commandoes massing on the border, ready to invade Natal. The Boers were alarmed but they allowed the marchers to pass along peacefully.

All along the route he ensured that justice was done and that provisions bought from local farmers and traders were paid for. At times he had to discipline men for theft or reckless behaviour, but a relationship of trust between himself and the “gang” was maintained.

Their trials and tribulations are documented in Elsabe Brink’s excellent The Long March Home, Kwela Books 1999.

Book Cover

The unwieldy column began its epic journey on Friday 6 October and the march finally petered out when several thousand half-starved mineworkers and their “families” staggered into Hattingspruit Station, 15 kilometres north west of Dundee, on 15 October, four days after war had officially been declared.

Marwick arrived in Pietermaritzburg the following day, still uncertain as to whether his employers considered his actions acceptable and if he still had a job! His effort was, however, officially recognised for the outstanding, even miraculous achievement that it was.

Marwick went on to form the Native Labour Corps on 14 December 1899, and joined the British Native Intelligence Department in Pretoria at the end of 1900. He was Native Commissioner in Johannesburg from 1902 – 1905.

The Zulus gave him the nickname “Waze wa muhle lo muntu” and he was given the name “Muhle”- “kind”, “the handsome one” and by extension “the one of a beautiful spirit.”

When he died in 1958, thousands of Zulus from all over Natal and Zululand made their way to pay their respects at his funeral, many of them veterans of the march or their descendents.

The Kwamuhle Museum in Durban is housed in the original building of the headquarters of the City’s Native Administration Department.

Kwa Muhle Museum (Visit Durban)

Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.